This is a short story that was originally published in an Anthology of writings by members of the Romantic Novelists Association titled ‘Loves Me, Loves me Not.’

The brief at the time was no more than 5,000 words and this comes in just under that. It’s a story set in 1149 at the unspecified domicile of John FitzGilbert the Marshal, the star of my novel A Place Beyond Courage. This particular story doesn’t involve him except in a cameo role but he does have a pivotal role to play!

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

A CLEAN START

SUMMER 1149

Sleeves rolled back exposing broad, meaty forearms, Florence heaved a bucketful of scalding lye solution into her washtub to mix with the cold water drawn earlier from the well. Humming to herself, she tested the temperature with a rapid swish of her fingers, and satisfied, stooped to the willow basket containing the first batch of laundry. Her lord and his wife had two sons and a baby in the cradle and what with tail clouts, swaddling bands and the ordinary tally of shirts, chemises, towels, sheets and bolsters, there was always washing to do. If Florence grumbled about her workload, it was usually with good-nature, for there was great satisfaction in turning a bundle of stained, stale linens into neatly folded parcels, soft, clean and gleamingly fresh. Thus far there was not a stain she had been unable to remove, from wine to hauberk-rust, to blood.

Pounding the first batch of garments in the lye water with her pole, she watched some youths training with spears and shields on the grass nearby, and unconsciously chewed her lip. Her son Adam was prominent among them, and fiercely aggressive, despite being one of the younger lads. The death of his father in battle four years ago had hit him hard. His grief and bitterness had fuelled a dark anger inside him and all he wanted to do was fight and have his revenge. People said to her that his rage was better expressed in the open and that in time he would change. All youths went through such times. Would she rather he clung to her skirts and shrank from the world? To Florence neither state of being was a preference, for both lacked balance.

Water sloshed over the side of the tub and darkened her skirt. Adam had lost his father and she her husband, her provider, her mate. He had been a serjeant, an ordinary soldier, beholden to John FitzGilbert the Marshal. One day he had ridden out behind his lord, and had not come home. He was buried in a communal grave near Winchester with all the others who had died on that day. She had no tomb at which to mourn. Lord John had returned badly wounded and life had changed forever, even while it continued the same on the surface.

She received a decent wage for her laundry work and she was entitled to eat and drink in the hall and have light for her small dwelling beside the kitchens. Her son was clothed, fed and was now receiving training at Lord John’s behest. He worked as a groom’s lad in the stables and when he wasn’t tending to the horses by which their lord set such store, he was practising his weapon play, so that when he was old enough and sufficiently skilled, he could take his father’s place among the foot soldiers. Florence prayed every night that by the time he was old enough to march out of that gate with an axe in his belt and a spear in his fist, the war would be over and peace restored. Adam would rise to become a senior groom, would marry and beget grandchildren to comfort her old age. But for the moment there was no comfort, only raw anxiety.

She poled a shirt from the lye tub, slapped it down on her laundry table and began beating it with a mallet to loosen the grime around the neckline and cuffs, her solid forearms shaking with each blow, her hands powerful and red. This part of the process was hard work but immensely satisfying. A vigorous bout of linen bashing usually dissipated most ills.

On the wall walk, the watchman sounded his horn, then lowered it, and bellowed urgently down to old Matthew the porter who hobbled to the doors and with help from a guard began to draw the bolts and lift the bar.

Florence ceased her labours and her stomach began to churn as the great wooden doors swung wide. Moments later her employer, John FitzGilbert pounded into the yard with his troop, filling it with the flash of mail, the bright colours of shields, the powerful smell of sweaty, hard-ridden horses. A couple of saddles were empty and they had wounded among the company. Lord John flung down from his stallion and began issuing rapid commands and Florence’s felt a flutter of panic. She wanted to run and hide, but stood her ground as the injured men were borne away for tending and someone ran for the priest.

Adam joined her as the crowd dispersed, his face pale with shock. ‘Eustace the King’s son has burned Rockley and our men were too few to stop them,’ he said, imparting what he’d heard from the dispersing soldiers.

Florence crossed herself. Rockley was one of their lord’s settlements on the Marlborough Downs, although there wasn’t much there beyond a couple of shepherding families and their flocks. ‘What about the people?’

‘Fled to safety, but most of the sheep have been slaughtered.’ His smooth young hand clenched around the haft of his spear. ‘I could have helped. If we’d had more men we could’ve….’

‘You are not trained,’ she snapped, her heart heavy with fear. ‘Look what happened to those who did fight. Look what happened to your father.’

He said nothing but a mulish expression crossed his face. ‘I have to help with the horses,’ he said abruptly and turned away.

Florence’s hands trembled as she picked up her mallet and resumed hammering her laundry, although she could barely see the garments through her tears. This wouldn’t do she castigated herself; this would not do at all. She bundled the chemise into the rinsing basket, then gasped with alarm as she saw Lord John standing to one side, watching her. Hastily she curtseyed and he bade her rise with an abrupt gesture. He had removed his mail shirt, but still retained the padded undertunic, streaked with grease from the iron rivets of the former. The upper left side of his face was terribly scarred where molten lead from a burning church roof had dripped over him and taken his sight on that side. His right eye, however, missed nothing. He had everyone’s measure from his senior knights down to the smallest pot boy pissing in the kitchen fire when he thought no one was looking. Just now, that measured, razor-sharp gaze was focused on her.

‘I have a task for you,’ he said, handing her a heavily blood-stained linen shirt. ‘I want you to clean this.’

Florence was taken aback – usually one of the lads belonging to the under-chamberlain would have delivered the item and the instruction. It obviously wasn’t her lord’s garment; there was no embroidery or pleating, and the linen was less fine. The lower right arm bore the heaviest staining and made her feel queasy.

‘I will do my best, sire,’ she said with a pragmatism she was far from feeling. ‘Salt and plenty of pounding will do the trick.’

He nodded curtly. ‘I trust you to do your work well. The man who owns this lost his hand to save my life.’

Dipping another curtsey, she frowned to herself, still puzzled. Why would her lord bring the shirt in person to her? Because it was an honour? But who was to see? Who would know?

‘When it is clean, take it to Hugh Fergant in the soldier’s dormitory,’ he added. ‘If he has other items for you to wash, then I rely on you to do so without asking. I will see you paid.’

‘Hugh Fergant is the injured man sire?’

‘He is.’ He started to turn away, then paused to look over his shoulder. ‘He has no kin to tend to him, so he is in our hands and I will have him properly cared for.’

‘Yes, my lord.’ Florence looked at the shirt. Hugh Fergant was new to the garrison and generally kept himself to himself, so she did not know him beyond a distant glance. She wondered if he would die. She shuddered at the thought that she might be washing a dead man’s shirt.

Taking the garment, she scrubbed and pounded, rinsed, added salt, scrubbed, and pounded again and again, until her hands were raw, her arms burning with effort, and sweat ran down her face like tears.

**********

Hugh Fergant’s bed was in the soldier’s dormitory – a wooden building set alongside the great hall to house the extra mercenaries that Lord John had employed to defend the keep. Florence made her way past the row of pallets and sleeping spaces until she came to the one at the end, set beneath a window with open shutters to let in the fresh daylight.

Fergant was propped against several pillows and when she arrived, was dozing, so she was able to study his beard-grizzled features without being scrutinised herself. Like her he was of middling years; old enough to have lines on his face and a seasoning of grey in his dark hair, but sufficiently young for his flesh still to mould his bones without drooping. A slight bend in his nose, indicated it had been broken at some point and had mended awry. His right arm was bandaged to the wrist and that was where it ended. No hand. No fingers.

‘I suppose I must grow accustomed to being the butt of stares,’ he said.

Florence jumped, flustered. ‘I thought you were sleeping,’ she said. ‘I did not want to disturb you.’

‘Do you always creep up on men to stare at them when they’re asleep, mistress?’

His eyes as he struggled to focus on her were the colour of mud, dark and fogged with whatever he had been given to dull the pain. A sheen of sweat glazed his brow.

Florence summoned her dignity. ‘My lord asked me to return your shirt and see to your laundry.’

‘Siegneur FitzGilbert is uncommonly generous,’ he said sourly.

‘Yes,’ Florence replied, her own lips prim. ‘He is.’

He dropped his gaze to the folded shirt in her hands. ‘At least he expects me to live to wear this again.’

‘Unless you take the wound fever, why shouldn’t you?’

He clenched his jaw and looked away from her. ‘What use am I like this? A soldier who cannot hold a sword?’

Florence drew herself up. ‘I had a husband once. ‘Would that he had had the opportunity to decide such a thing.’

‘And what do you think he would have chosen?’

The question was like a slap and made her draw back with a gasp. Without a word, she turned from him and walked out. Once in the fresh air, she inhaled deeply, clearing her lungs of the stifling weight of the soldier’s quarters. She felt weak, sick, and shaky. Angry too. At Hugh Fergant, at her lord for putting this burden upon her, and at herself most of all. She had thought she was done with mourning, but tentacles of grief still lurked in hidden corners, waiting to catch her unawares and send her spiralling into misery. What indeed would her former husband have chosen? She didn’t know, and she never would.

Looking down she realised that the shirt was still in her hands and she had fled without Fergant’s soiled laundry. Lips pressed together, Florence turned and marched back into the building, her skirts billowing with the vigour of her step.

He was slumped on his pillows, his eyes squeezed shut and his mouth tight with pain. She placed the folded shirt on his bed. ‘Sometimes it is not the things that are taken away, but the things that remain that define a man,’ she said, her tone peremptory because she was so upset.

He didn’t open his eyes. ‘Does that apply to a woman too?’

Florence grabbed the bundle of soiled linens piled beside the bed and stalked out again. When she set to work on her laundry, it was with a renewed will and forceful, angry relish.

**********

Four weeks later, Hugh considered his bandaged arm and grimaced. He would not think the word ‘stump’ for the place where it ended. He would not dwell on the fact that a month ago there had been a hand and fingers that knew the tactile pleasure and strength of holding a weapon and lifting a cup. There was no point thinking that way. The laundress had been right when she berated him. It was indeed what remained that defined a man.

It had taken him an age this morning and much fumbling and cursing before he had managed to fasten his hose to his drawers, but he had succeeded. Another small triumph and a salutary lesson in how much he had taken for granted before. Having struggled into his tunic and smoothed his hair, he picked up the little carved pot of walrus ivory he had asked one of the men to obtain for him in the town. It rested in his palm, solid and delicate at the same time, and it made him smile before he closed the fingers of his good hand over the interlacing on the lid and left the dormitory.

Florence was in the yard, bustling the dust from her laundry shelter with vigorous sweeps of a besom broom. Watching the robust motion of her arms, a pleasant warmth suffused Hugh’s solar plexus. Although she was frequently prickly with him, he had come to value and enjoy her visits during his convalescence, and he even dared to think that she enjoyed them too, despite their initial rough start.

Inhaling deeply, he strolled across the yard, feigning nonchalance, but less certain within himself.

At his approach, Florence ceased her sweeping and a look of pleasure brightened her face. She had strong features – a big nose, square jaw, thick black brows. Everything about her was stalwart, but amid all that vigorous practicality, her eyes surprised and fascinated him for they were like agate jewels, flecked with tones of green and amber and gold.

‘A fine morning,’ she said. ‘How are you today?’ Her smile of greeting exposed good teeth apart from a small chip on an incisor.

Hugh shrugged. ‘I am managing, mistress, and for that I have you to thank.’

‘What for doing your laundry?’

‘For shaking me out of my self pity and being good company.’ He cleared his throat gruffly. ‘I wanted to tell you that my lord has offered me a post as gatekeeper. Matthew is feeling his years and my lord wants a younger man to learn the duties and take over in the fullness of time. It’s a task that a determined man with one hand and a hook can accomplish well enough.’

‘Oh, that is good news, I am pleased for you!’ She leaned forward to touch his arm, her vivid agate eyes warm with pleasure.

‘I wanted to give you this.’ Awkwardly, He held out the pot and watched her face change. Her complexion, already ruddy, flushed until her cheeks were scarlet. Biting her lower lip, she took the pot from him gingerly and cupping it in one large, work-roughed hand, uncapped the lid with the other. A warm, sensual perfume wafted from the pale unguent within.

‘It’s a rub for softening the skin. I thought you would like it.’

She said nothing for a moment, and then she gave a small laugh and her chin quivered. ‘I do, indeed I do.’ Her voice had a catch in it, ‘but I think it is a lost cause on a laundress.’

‘There is no such thing as a lost cause, as you told me yourself, and as our Seigneur would tell you too. It is good to have special things in the world.’

Florence blushed again, then smiled at him, and he thought he had never seen anything so beautiful in his life.

**********

Although busy over her laundry vat, Florence still found time over the weeks to watch Hugh learning his new trade with Matthew the gate keeper. Hugh was deferential and respectful to soothe the old man’s pride. Matthew was prickly and authoritative, but they seemed to have reached an accord, even while not being bosom friends.

Smiling a little wryly, Florence gazed at her hands which, as usual were red and chapped from their constant immersion and scrubbing. Not all the perfumed unguent in the world was going to make a difference, but in other ways, she had not felt the same ever since dipping a first tentative forefinger in the pot when the luscious scent of roses had made her senses swim.

Her son paused at her side on his way to battle practice. ‘I don’t know why you’re so taken with him,’ he said in a surly growl.

Florence eyed her son with mingled anxiety and exasperation. ‘He is a good man. He’s doing very well at gate duty.’

‘Hah!’ Adam snorted. ‘He’s just letting Matthew order him around.’

‘He’s letting Matthew teach him the job, which is as it should be, and he’s being careful of Matthew’s pride.’

Adam’s lip curled. ‘He’s a useless cripple,’ he said viciously.

Florence gasped at her son’s venom. ‘How dare you say such a thing. I am ashamed of you!’

Adam’s complexion reddened. ‘You should be the one ashamed, Mother, the way you fawn on him. My father was twice the man he is. Do you think he would have approved!’

‘Your father is dead,’ Florence snapped, wondering how many more times would she have to say those words and feel the cut. That too was like an amputation. ‘Life has to go on.’

‘He’s useless!’ Adam reiterated, his voice holding a desperate wobble. ‘Lord John only keeps him out of pity.’

A hard hand gripped Adam’s shoulder from behind. The fingers were long and elegant and the middle one was adorned by a gold ring set with a green beryl. Adam spun round, stared upwards, then bowed his head. Florence dropped a curtsey. ‘My lord.’

John FitzGilbert transfixed Adam with a fierce, one-eyed stare. ‘Better men than you put bread on the table,’ he said. The pitch of his voice was normal, but the tone was frigid and each word as clear as ice. ‘Hugh will learn to fight left- handed as I have learned to fight without half of my vision. When you have his bravery then you will not need to criticise and then I might think you worth something.’

Adam flushed scarlet. The Marshal gave a brusque nod, turned on his heel and strode off towards the stables.

Florence reached for her son, but he shrugged her off and stamped away in the opposite direction to the one their master had taken.

Sighing, Florence returned to her laundry and resolved that she would speak to Adam once her work was done and he had had time to think about what had been said. The matter had to be resolved before it could fester further.

**********

Sniffing back tears of humiliation, determined he would not openly cry, Adam gathered his belongings. He refused to stay where he wasn’t wanted. Barons were always looking to hire warriors and Lord John wasn’t the only one around. He could use as a spear as well as any man – better than many. He was tall and strong for his years. They’d want him in Devizes or Winchester for certain.

After a glance over his shoulder to make sure no one was looking, he opened his mother’s clothing chest and rummaged past her chemises and folded gowns until he found the pouch containing his father’s round silver cloak brooch. He tipped it into his hand, stared at it for a moment before securing it to his mantle high on the shoulder in the style of a warrior. It wasn’t stealing; he was only taking his rightful inheritance. Nor was it stealing to take his father’s shield from the wall behind the bed box, or the long knife with the tabby patterned blade that had belonged to his grandsire. He wasn’t going to leave them behind for Hugh Fergant to use.

The gates were open and Matthew was dozing by his watch fire. There was no sign of Hugh, and Adam experienced a surge of satisfied contempt. Fine guards these were. If he was an invader, he could have ridden in and massacred everyone by now.

Three beggars were huddled in the lee of the castle wall, awaiting hand outs of bread from the almoner. They were so much a part of the landscape these days and Adam was so caught up in his own discontent that he paid them scant attention.

However, they were not so dismissive of him and the silver cloak brooch glittering on the crest of his shoulder…nor the fact that he appeared to be alone.

**********

Hugh returned from an errand to the stables and stood by the gate, observing the bustle in the outer ward. Florence had just carried a basket of washing across to the drying frames near the well and was hanging up sheets and towels. He admired her strong, ample curves, imagined his hands at her waist, and himself in possession of all that generosity. Behind him, old Matthew hawked and spat into the fire, making it sizzle and hiss. ‘Yon laundress’s lad’s gone off as if he means business,’ he remarked.

Hugh turned, a cold prickle between his shoulder blades, the same one he always felt before a battle. ‘’Gone where?’

‘Didn’t say.’

‘How long since?’

The porter pointed at a spot on the wall behind him. ‘Since the sun shadow was there. Looked to me as if he was going some way. He’d got a spear and shield with him, and he was wearing his cloak. Fancy brooch too.’

Hugh shook his head in exasperation. ‘Why didn’t you stop him?’

Matthew shrugged. ‘No reason to. Not my business.’ His eyes gleamed. ‘Thought you might find it easier to be rid of him anyway.’

Hugh clamped his jaw on the retort that Matthew’s wits were addled if he thought the lad’s disappearance would aid his relationship with Florence. Muttering under his breath, he hurried to the stables and ordered a groom to saddle up his bay gelding. ‘Make haste,’ he said and cursed that he could no longer fasten buckles and cinches himself.

‘The lads have been riding him out and about while you’ve been sick,’ the groom said. ‘He’s still got a bit o’ stable belly, but he’ll do.’

Hugh nodded curtly and set his foot to the stirrup ‘He’ll have to.’

It was simple enough to guide a horse one-handed and Hugh was an accomplished rider. A man had to be to follow John FitzGilbert. Even so, he felt vulnerable as he rode out of the keep gates and a part of him knew this was outright folly. What was he going to say to the boy? What if it came to blows?

A few enquiries at the gate, abetted by his own instincts, set him on the track across the Downs towards Devizes which was the nearest town of any size. The route was beautiful now in the summer, the grassland lush and the sheep grazing with voracious intent, their lambs gambolling in groups or stretched out sleeping on the grass. In winter, the road was often a lowering bleak place, beset by bitter winds and snow drifting against the great grey standing stones that had been built by giants.

He trotted into a dip, rounded a sharp turn in the path, bordered by an alder thicket and stared in momentary shock at the sight of Adam being menaced by three ragged figures, knives out, intent on robbery.

‘Hah!’ he cried to the gelding and dug in his heels. Controlling the horse with his thighs, he swept off his cloak. The men turned to the sound of hooves but Hugh was already upon them. He threw his cloak over the man to his left, rode down the middle one and put the horse between the youth and the third attacker.

‘Put your foot on my stirrup!’ Hugh shouted.

Pale as whey the lad set his foot over Hugh’s. The latter’s powerful left arm and strong hand grasped him and hauled him up and across. ‘Go, Bayard, go!’

The gelding, a veteran of many skirmishes, responded to the tone of voice and touch of heel with a burst of speed that left their attackers floundering. A glance over his shoulder showed Hugh that the man he had ridden down had not risen again. He had lost a decent cloak and the boy had sacrificed his shield and spear, but a patrol party could easily recoup them.

‘How did you know to come after me?’ Adam asked as Hugh reined the gelding back to a brisk walk.

. ‘It’s my duty as gatekeeper to know all that comes and goes,’ Hugh said, deciding not to mention old Matthew’s part in this. It better served his purpose to have the youth think him omniscient.’ He gave the lad a considering look. ‘I thought you had more backbone than to run away.’

Adam’s jaw tightened with defensive pride. ‘I wasn’t “running away” – I was leaving – that’s different.’

‘Because I am courting your mother?’ Because of this?’ Hugh raised his mutilated arm. ‘I have no choice but to live without my right hand for the rest of my life, but I will make the best of what I do have. Do you know how easy I would have found it to whimper in a corner and lick my wounds?’

The youth looked away, and the knot in his throat moved convulsively.

‘I have no quarrel with you,’ Hugh said in a gentler tone.

The boy’s expression contorted with a struggle of emotions. ‘Back there,’ he said with grudging admiration. ‘You knew what to do.’

‘’I’ve fought enough battles lad. You don’t follow the lord Marshal if you can’t handle yourself.’ He took his hand off the rein to grip the boy’s shoulder. ‘You’ll know what to do next time too.’

Adam nodded stiffly. ‘Yes,’ he said, and then in a subdued voice, ‘Thank you.’

Hugh said nothing, but squeezed the thin shoulder under his hand. ‘Then no more need be said.’

**********

Florence was waiting anxiously by the gate when they rode in, and as soon as they had dismounted, she flung her arms around Adam, weeping with relief. Crimson with embarrassment, the youth stood effigy-stiff in her embrace and then pulled away.

‘Don’t fuss woman,’ Hugh said with a conspiratorial man to man glance at Adam. ‘All’s well.’

Adam nodded agreement and scuffed his feet on the ground.

After her initial burst of relief, Florence had the wisdom to hold her tongue. Clearly Adam and Hugh had reached some kind of accord, although she noticed that Hugh was missing his cloak. Doubtless, she would hear the story in the end.

**********

That evening, Florence took a chicken pasty and a jug of ale over to the watch fire. Old Matthew was snoring under his canvas shelter, but Hugh was hunched over the flames, now and then casting a piece of firewood onto the hot ember-bed.

‘How’s Adam?’ He made room for her on his bench.

‘Asleep,’ she replied. ‘He says you saved him.’

Hugh rested his forearms on his knees. ‘He’s learned some hard lessons today, but all to the good and it’s over now. Best to let it rest and move on. It’s a new day tomorrow.’

Florence held her hands out to the fire. ‘The signs say it will be fine.’

‘Good washday then.’

Florence watched him unwrap the pasty from the cloth, dexterous despite his handicap, and take a full, appreciative bite. She wanted that kind of hunger to fill her life again… desired it. ‘I think my lord intentionally gave me your shirt,’ she said with a thoughtful frown.

Hugh chewed and swallowed. ‘He always pays his debts with interest,’ he agreed. He wiped his hand on the cloth and took her right one within his grasp. ‘If the weather’s set fair for the next few days, perchance there will be time for a wedding too.’

‘Perchance,’ Florence said with a smile, and leaning her head on his shoulder, watched the sparks climb on ropes of smoke towards the stars.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

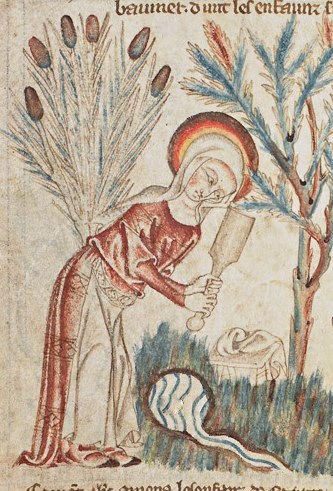

Top illustration is of a woman doing her laundry, Holkham Bible 14th century, British Library.