A while ago, I I attended the Romantic Novelists Association Conference at Harper Adams University Telford where I gave a powerpoint talk on how I write historical fiction and I said I would share it on this blog – so without more ado, here it is.

I write historical fiction for a living and have been doing so since the early 1990’s. I’ve had my ups and downs, but averaged out over the years, I have been able to pay the mortgage and keep my 3 dogs in biscuits!

I am going to tell you how I write historical fiction and recreate past lives and times. I don’t expect you to agree with me throughout and don’t take this as what you yourself should do. If you disagree with my opinion or views that’s fine. Everyone has their own path to follow and there is no single right way. But this is what works for me, and what works for me is still something in constant progress.

I need to go back to the beginning.

I came to historical fiction in my teens via visual media. I didn’t read much historical fiction as a child unless you count myths, legends and the hero’s journey but I had always loved historical adventure films – Robin Hood, the Vikings, El Cid. In my early teens the BBC aired The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Falling hard for Keith Michell as the young Henry, I was inspired to begin writing a Tudor story. However, I didn’t get very far and put it away after the school holidays even though I’d enjoyed the experience.

By this time I had begun to read historical fiction. Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave had a huge impact on me and I also became engrossed in the Angelique novels by Sergeanne Golon, Juliet Benzoni’s Katherine series, and the works of Anya Seton and Nora Lofts.

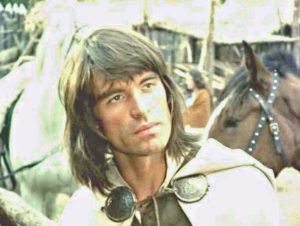

Then along came Arthur of the Britains starring the gorgeous Oliver Tobias

And finally, the catalyst. Desert Crusader featuring Andre Lawrence as Thibaud ‘Le Chevalier Blanc.’

You can watch episodes on Youtube under the original French title Thibaud Ou le Croisades. It was set in the 12th century and starred a handsome knight in flowing white robes galloping round the Holy Land enjoying various adventures of romance and derring do. Aged 15 now and with hormones running riot, I fell totally in love and began writing what I guess amounts to a fan fiction story. However, it swiftly developed a life and character of its own and gradually, over a timespan of around a year, it turned into a novel. I didn’t know anything about the Holy Land in the 12th century and so I had to begin researching because I wanted my story to feel as real as possible to me. I was using my imagination but that imagination had to feed from knowledge and reality. Every genre has its rules, structures and boundaries and every genre, including fantasy has to be researched. In order to use your imagination on the canvas, you have to have a canvas to begin with, and the threads and the colours you choose to illustrate your story will determine your finished article. Your imagination might stitch the story, but the threads and colours are the research.

You can watch episodes on Youtube under the original French title Thibaud Ou le Croisades. It was set in the 12th century and starred a handsome knight in flowing white robes galloping round the Holy Land enjoying various adventures of romance and derring do. Aged 15 now and with hormones running riot, I fell totally in love and began writing what I guess amounts to a fan fiction story. However, it swiftly developed a life and character of its own and gradually, over a timespan of around a year, it turned into a novel. I didn’t know anything about the Holy Land in the 12th century and so I had to begin researching because I wanted my story to feel as real as possible to me. I was using my imagination but that imagination had to feed from knowledge and reality. Every genre has its rules, structures and boundaries and every genre, including fantasy has to be researched. In order to use your imagination on the canvas, you have to have a canvas to begin with, and the threads and the colours you choose to illustrate your story will determine your finished article. Your imagination might stitch the story, but the threads and colours are the research.

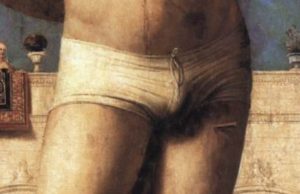

In order to visualise the world my characters lived in, I had to know the history to make a pattern on my blank canvas and select the right threads. The more I researched my subject, the more interested I became and the more I wanted to know about the period. And the deeper I delved, the more I began to discover that what I’d been taught in broad brush stroke in school and from general media was not always what the more in depth history portrayed. Often what was out there in public was years behind current research, or just repeated in ignorance. In my own period of interest I discovered that contrary to what commentator Dorian Williams had said on the Horse of the year Show, the warhorse of a medieval knight was not some galumphing great shire beast, but a much smaller animals of around 15 hands high, more akin to a modern Welsh cob. I discovered through the works of Ewart Oakeshott that a knight didn’t have to have muscles like Conan the Barbarian to wield a sword because the average sword of the 12th century weighed about as much as a tennis racket and was used with similar skills. It’s probably no coincidence that Viggo Mortensen in Lord of the Rings who had never fought with a sword before, picked it up so quickly – because he was a champion tennis player. Lord of the Rings might be fantasy and the sword fighting Hollywood choreographed, but it’s essentially 12th century kit.

Learning all these new things and in many cases relearning was an intoxicating experience because it was opening up a whole new world to me. I’ve been researching for 45 years now and I realise that the more I research, the more is left to know.

Of course, if you are writing a historical novel, it is not about dumping all that knowledge and research into the text. That’s the last thing you want to do. Your aim is to entertain readers with a riveting story, not bore their socks off. Research is about informing yourself so that you can walk with confidence in the world you are creating. It’s about credibility. Robert McKee in his lectures on story structure for script writers says in his 10 commandments that ‘thou shalt know your imaginary world as well as God knows this one. Well that can sometimes be a problem – knowing this one – but you get the gist!

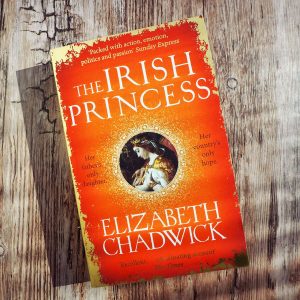

A 14thc bridge below the Abbey of Tintern de Voto, Southern Ireland, visited while I was researching The Irish Princess

Authors of historical fiction are bridges between the reader and the past and this is true whatever area you write in. Readers’ tastes are wide and varied and what they want and what you yourself are drawn to write, will affect the kind of bridge you build for them. Some readers are only after light entertainment when they come to historical fiction. They want a great story, but basically they are quite happy with a fancy dress background. They want the gleam of pearls on a gown, the sultry glance between hero and heroine, they want the romance and derring do and aren’t bothered if there are historical mistakes, or indeed wouldn’t recognise them.

However, others will be looking for rich and detailed novels that explore the past in more depth and realism.

Sometimes the bridge you build will attract readers who really should be crossing a bridge better suited to their personal requirements and expectations. I have seen reviews for my novel The Greatest Knight saying “I was expecting more romance. I wanted to be wooed by the hero.” And then another reader said. “This novel is too romantic.” Or “There’s too much fighting.” Or There’s not enough fighting.” You have to take on board that you are not going to suit every reader’s taste and readers bring their own ideas, background and prejudices to the reading of your work. You can’t legislate for each one individually. You just have to build your bridge the best you know how and and build it with integrity. Don’t sweat the stuff that’s out of your control.

So, how best to please the people who do walk over your bridge who you are hoping will enjoy the experience and return your way often. You need to cater to both the ‘don’t care as long the story’s good and the frock’s pretty’ brigade and the ‘But the sleeve on that dress is ten years out of dateline’ geeks.

One of the sayings that irritates me is when people talk about historical fiction and say ‘If I want facts, I’ll look in a history book.’

Sometimes, to judge by the history books I did look in while doing my research on Eleanor of Aquitaine, chance would be a fine thing, but that’s something for another discussion.

Yes, story is massively important, but in the case of historical fiction the story must rest solidly on historical integrity. Note that I don’t say accuracy because that has different connotations. With the best will in the world, no author can get everything right, but there’s nothing to stop us from obtaining a thoroughly good grounding in our chosen period and doing the best we can. Indeed, it’s essential. If you are twisting history to suit the story then you’re not a good enough writer. Part of the absolute fun of being a historical novelist is working out how to weave history and story together so that the facts are not distorted but the story remains so good that you’re going to make people lose sleep over it. ‘Just another page before bed-time until 5am!’ Story and historical integrity and authenticity – that’s another word, do not have to be mutually exclusive. They are stronger and better together. Part of the utter joy of being a historical novelist is working out how the narrative can be woven in such a way as to keep the historical facts and details intact without sacrificing story and vice versa. Work with the facts, work around them if you must, but don’t distort them. If you do your research and don’t warp the history while telling a bloody good story, then the historical detail anoraks will stay off your back, the people who just want the frocks and a story won’t notice, and everyone’s happy.

When I first began writing historical fiction, I wanted my characters to live in a world that felt real to me. However, my early work was still very much a case of characters wearing the right clothes, wielding the right weight of sword, riding the right horse. The mindset of the period had yet to develop. I was working with an elaborate dressing up box to be sure, but my people were still thinking in modern ways. As I read my way through various research works and moved from my teens into my twenties, I began to look at mindset more. I stopped asking myself what I would have done in a particular situation, but asking what they would have done? How would it feel in 1200 to be 14 years and be told that I had to marry a man in his 30’s? I would be terrified and grossed out, but how would my 12th century person feel? Very possibly the same, but what alternatives might her culture and upbringing bring to the mix? What might be the responses of those around her? If she refused or threw a tantrum about it then she might find herself punished and seen as a disgrace to her family. Or, she might feel nervous but proud to do her duty for her family and go through with it for her dynasty. She might feel pleased to have a strong protector. She might feel honoured. You have to get under the skin of that society and look at how it functioned. You have to think outside of your own box and into theirs and bring the reader with you over the bridge into that world. You have to become a native speaker, not a tourist.

So, how then do I go about researching a historical novel?

It’s a blend of many aspects, and we are currently blessed with more information than at any other time in history even if the piddling little fact that we really need to know is often hidden away in a JSTOR article that we can’t access.

I digress. I have a manyfold approach to the historical research that goes into my novels.

1 I read primary source. For my period it’s mostly ecclesiastical with a few bits of secular writing here and there, so one does have to take into account the biases of the church, and one should also know the biases and background of one’s particular chronicler or writer. Gerald of Wales for example is a man with a poisoned pen and the mentality of a tabloid journalist. One should always, always doublecheck his statements and ask is this at face value? Why was Gerald saying this? What were his thought processes? What’s fiction, what’s fact? Always question whatever you are reading and that goes for any century. The primary sources will give you an idea of the mindset of the time the thoughts behind the world in which your characters live – politics, social attitudes. It helps to look at the world from both sides of an argument. To look at the pros and the cons, because one size never fits all. I read widely in primary source because it helps me tune in to the period, and it’s fun.

Primary source illustrations are brilliant too. There are stories and daily living clues in illustrations. I can disappear into these for hours and have to discipline myself!

The same goes for museums. Go and take a look at what’s on show and immerse yourself. Ask yourself about the objects. How were they made? Who used them? What were their daily lives? Carry a camera everywhere.

2 Secondary Source

This is where all the academic works come in covering a broad spread from the life and personal times of the person I’m writing about to wider social and detail issues. It also brings in archaeology which straddles the line between primary and secondary. The finds are primary but usually have to be interpreted by experts.

The things they touched and handled. Where were they found? What are they made of? What were they for? How were they used? Who used them?

Again, read around the subject from several angles. Get to know who is respected on your need to know subjects and who is less reliable. One of my tips for any sort of reading when you’re writing historical fiction, is not just to read the books that you know are essential to your novel, but to browse material as a matter of general interest. I pick up no end of interesting books on my core mediaeval subject matter just by pottering, and they always come in useful at some point. For example this one…

Which has various details including the story of Roland the Farter, a man who actually lived, and held his lands for the task of coming to court each Christmas to perform a leap a whistle and a fart in front of the king, was a great source for a moment of light relief in one of my works.

I research on Internet.That has some wonderful resources these days and I expect everyone here uses it extensively. When one’s been doing it for a while one tends to develop and inbuilt crap detector and know which sites to avoid. The Internet has made a terrific difference to the amount of primary source material available online and has made making connections with academics and experts so much easier.

I go to places to gain a feel for the lie of the land, for what was there before, and to make a physical connection. I can’t get to every place I’d like to go on writing a novel, but I try and visit a selection. I’ve just returned from South-East Ireland where I’ve been researching for the work in progress. I buy the guidebooks and think myself into time and place.

The other thing I do is to re-enact with early mediaeval society Regia Anglorum. This brings artefacts out of the museum and into 3-D. You can interact with replicas and find out how it feels to use it. For example I have an earthenware cooking pot replica with a late Saxon and early Norman dateline. If I ever need to write a scene with one of these, I know how it will react on a fire because I’ve tried it out for myself. I know its touch and feel and behaviour, so it brings that 3D reality into the equation.

Then I add in that all important ingredient of imagination (which is your own recipe. I can’t help you with that one!) pick up my needle, thread it and begin to sew the story. The amount of research I have conducted enables me to create that picture with confidence. The main technical points during that creative process, my dos and don’ts are as follows.

1 Don’t info dump. Take all this research, turn it into an essence and use it judiciously like the best perfume. You are using all the research you have done to inform your choices, not to show the readers how clever you have been. I used to slightly indulgently info dump when I began my career. I’d add in bits of medieval Welsh because it interested me or I’d forget to make it clear what a hauberk was, or braies. So always make it clear what you are referring to and you don’t always have to use the exact phrase. Try and avoid ‘As you know Bob’ moments when including the need to know history. Don’t have one character saying to another ‘As you know Henry, I married you in 1151 and we’ve had 3 children since then, one named Richard born last September.’ The need to know information should generally come from your characters and what they know, but in a natural way, or be a seamless part of the narrative. A paragraph of history lesson can put readers off.

2 Make sure your characters realistically reflect the times in which they lived. Don’t make them modern people in fancy dress unless you’re specifically writing for readers who want that experience. If you know your readers prefer the Disney variety of history then well and good. That’s the bridge you have built and you know what you are doing. Otherwise make sure the people are of their time by doing your research (see above).

3. If you can’t find something out, don’t let it stall you. Use your best guess. If you have done the research, then your best guess is likely to be plausible. Sweat it, but don’t kill it in other words. I always ask myself on a scale of 1-10 how likely a character is to have done such and such or how likely is this to have happened? If the answer is between 8 and 10 I’ll go with it. Anything less and I find another way – and it is actually satisfying and fun to do – like a jigsaw puzzle.

- 4.Senses. Use them. The touch, taste, feel, sound, sights of the time are vitally important in giving the reader the sensory experience of another world. They are a major building block of your bridge. What was the smell of a particular town when your character entered it? Was it familiar or unusual? What was their favourite taste or colour? What fabrics and colours could their station in life afford? How do reins feel between the fingers on a wet day? How would your character react to such things in the context of their time period? Check how your character would react to these things. It’s an areas that brings life and empathy to creating the past. Even the horrid stuff is still a treasure chest. For example This piece is from a recent work: TEMPLAR SILKS.

The summer downpour dimpled the surface of the Thames and shadowed the water with the hues of a dull sword. William had crossed the bridge from the Southwark side with his small entourage and they had immediately been engulfed by the ripe smells of the wet city, a perfume so robust and complex that it raised the hairs on his nape, simultaneously attracting and repelling. Ordure and excrement, the brackish, muddy waft of the river shore at low tide

5. Language.

A knotty one. I would say don’t use twisy twasery and don’t use ultra modern slang. The latter can work in some cases but only if you really know your subject and your genre, and your readers are in cahoots with you. Think very carefully. Plain, serviceable English tends to be your best tool. The more my career has progressed, the less deliberate ancient language I have used and now if I do use it, I make very clear what the word actually means. You can do beautiful things using bygone language, but you need to be very clear about what you are doing. I’m not saying don’t use it, just have a clear game plan and just insert the occasional word to give a flavour. Read works of the period to get an idea of the flow of the language. You’ll pick it up by Osmosis.

6. Depth. Don’t just take one source, take several. Don’t be satisfied with the superficial report. Always look underneath – unless again you are writing a novel that doesn’t require in-depth research. Be aware that what you do find out will colour your writing and change the story. For example: When researching Eleanor of Aquitaine, some of her biographers said she had two illegitimate half brothers – and cited evidence in primary source documentation. I went to check that documentation and discovered that it had been misread and that actually the half brothers in question were concerned with someone else entirely. ‘Brother of the Queen’ didn’t mean Eleanor! If I hadn’t gone digging, I’d have given relationships and scenes to men who had nothing to do with Eleanor of Aquitaine whatsoever. So always be aware that what you research will colour the finished article. I guess that there are many kinds of truths and they can all look different. So you have a horse chestnut tree – that’s one truth. And it produces a spiky green casing – that’s another sort of more concentrated truth. And then inside that casing there is a very different shiny brown fruit. They all look very different, and they’re all versions of the truth. You have to decide which version to tell and how deep you want to go. And that will depend on you yourself and your audience.

In the end it all boils down to doing the research, especially in terms of mindset. The more you do, the more colours you will have to work with and the greater scope you will have for your imagination and the more seamless and harmonious will be the blending of story and history. The rest of it, the stitching and the bridge building are up to you!