Mahelt (Matilda) Marshal, William Marshal’s eldest daughter does not have the fame or resonance in history that falls to her illustrious father but that does not make her any less fascinating and I made her the subject of my novel TO DEFY A KING, the story of two families, the Marshals and the Bigods, and their conflicting loyalties on the road to Magna Carta.

Like most women of the medieval period, Mahelt is little mentioned in the narrative historical record. However there are various charters and documents that give pointers to her character and her life – scattered bones that when collected and assembled, offer a glimpse of her personality and illuminate the path even 800 years after she stood on the wall walk at Framlingham, or played on the banks of the River Wye at Chepstow as a little girl.

We do not have a birth date for Mahelt, but it is highly likely that she was the third child and first daughter of William Marshal and Isabelle de Clare. Their first two children were boys; we know that. William Junior was born about 9 months after his parents’ marriage in the late spring of 1190. His brother Richard followed some time in 1191. Given recovery dates and gestation periods I postulate that the earliest Mahelt could have been born is summer 1192, although I think it probably later than this. In THE GREATEST KNIGHT I’ve given a date of 1194, but I’ve revised this now and think she was most likely born some time in 1193. One of her father’s sisters was named Matilda/Mahelt and she may have been named after her.

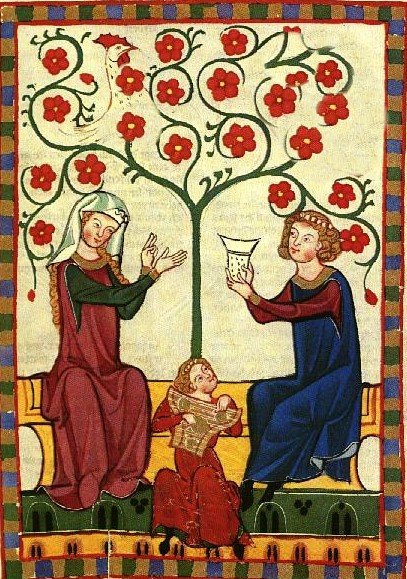

Was there a special relationship between William Marshal and his firstborn daughter? I think there was. The Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal completed around 1226 says of Mahelt that she had the gifts of ‘wisdom, generosity, beauty, nobility of heart, graciousness, and I can tell you in truth, all the good qualities which a noble lady should possess.’ These are the usual formal stock in trade descriptions used by chroniclers and as such I take them with a pinch of salt. However, the section also adds ‘Her worthy father, who loved her dearly, married her off, during his lifetime to the best and most handsome party he knew, to sir Hugh Bigot.’ This is interesting because following on from this, the other daughters and their qualities are mentioned, but there is no more of the ‘loved dearly’ business. Mahelt is the only daughter who receives this accolade. The Histoire says of Mahelt when her father was dying: ‘My lady Mahelt la Bigote was so full of grief she almost went out of her mind, so great was her love for him. Often she appealed to God, asking Him why He was taking away from her what her heart loved most.’ And then later, his daughters are called for to sing to him and the Marshal says: ‘Matilda, you be the first to sing.’ She had no wish to do so for her life at the time was a bitter cup, but she had no wish to disobey her father’s command. She started to sing since she wished to please her father, and she sang exceedingly well, giving a verse of a song in a sweet, clear voice.’ The other daughters are not mentioned save for the youngest, Joane. Indeed, re-reading the text with a closer eye, it appears that only Mahelt and Joane (a little girl at this stage) were sent for to sing for him. I suspect these would be the daughters he knew best of the five, both having belonged to times in his life when he had the opportunity to be more at home and watch their formative years.

Of course one couldn’t let such bonds get in the way of politics when one was a 13th century magnate and product of one’s times. When William went to Ireland in 1207, he had to decide what to do for the best with Mahelt who was now of marriagable age. William approached Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and ‘asked him graciously, being the wise man he was, to arrange a handsome marriage between his own daughter and his son Hugh. The boy was worthy, mild-mannered, and noble hearted and the young lady was a very young thing and both noble and beautiful. The marriage was a most suitable one and pleased both families involved. It’s interesting that William approached Roger Bigod, not the the other way around.

At this stage Hugh Bigod would have been about 25 years old. Reading between the lines, it was indeed a shrewd and good match. The Bigods were in favour with the King and had a royal kinship tie in that Ida, Countess of Norfolk was the mother of William Longespee, Earl of Salisbury – King John’s bastard half brother. So Hugh Bigod was half-brother to the King’s half-brother. Longespee was also kin to the Marshal family through marriage as his wife, Ela, was William Marshal’s cousin once removed. The Earl of Norfolk was rich and powerful and East Anglia where he dominated, was almost a kingdom on its own, rather like the Marshal’s grip on Pembrokeshire or Leinster.

Nothing is known of Mahelt’s life at Framlingham after her marriage. We know she bore a son, Roger, in 1209, two years after her marriage, and then another son, Hugh, in 1212 and a daughter Isabelle in 1215. There was also a third son, Ralph. We can glean from this that her first child was born when she was about 16 and obviously conceived at a younger age. Her second when she was 19, her third when she 22. The three year gaps are interesting. Did she breastfeed? Did they practice abstinence? Was Hugh away a lot? More food for the novelist’s thought.

During the Magna Carta crisis of 1215 and the Civil war beyond, leading up to the death of King John and then the minority of Henry III where the regent was actually Mahelt’s father, I wonder how Mahelt managed to balance her life. Her new family, the Bigods, were opposed to King John, as was her brother, William. What must she have felt about having family members on both sides of the divide? In 1216, Framlingham was besieged by King John and the castle swiftly capitulated. It is known that one of Mahelt and Hugh’s sons was taken hostage – presumably Roger the eldest. Where was Mahelt when this happened? We don’t know. Her father in law was in London – or headed that way, but certainly not at home. We don’t know where Hugh was either, but not at Framlingham. Having seen her brothers taken hostage by King John, knowing what happened to Maude de Braose (starved to death in a dungeon with her son while John’s hostage), I wonder what her response was. Perhaps the awareness that her father was one of the backbones of King John’s regime might have been a comfort in that King John was hardly going to do away with the grandson of a man he needed.

In some ways working through the research is like assembling lots of small fragments of bone that will eventually make a whole person.

Outside the scope of TO DEFY A KING, but affecting Mahelt’s life in maturity, was the death of her husband Hugh Bigod at only 43 years of age. It was sudden. One minute he was very much alive and attending a council at Westminster. A week later he was dead, leaving Mahelt a widow at the age of 32 with three, possibly four children, the eldest of whom was 16 years old. Mahelt moved swiftly – or those around her did and within three months of her widowhood, she married William de Warenne, Earl of Surrey. He was the Bigod’s neighbour with lands in Norfolk and Yorkshire and castles at Castle Acre and Conisburgh. He was considerably older than her – by my reckoning he was at least 60 years old. Mahelt bore him a son and a daughter – John and Isabelle. I find it very interesting that in all of her charters at this time, she calls herself ‘Matildis la Bigot’ never ‘Matildis de Warenne.’ or only as an afterthought. For example: A charter dated between 1241 and 1245, following the death of her second husband has the salutation ‘….ego Matilda Bigot comitissa Norf’ et Warenn.’ The ‘Warenn” is an official title like the ‘Norf’ The Bigot is her personal name. Even her second husband called her “Matildis Bygod.”

The latter does actually change in 1246 when she was granted the Marshal’s rod by King Henry III. All of her brothers and sisters were dead and the hereditory Marshalship of England came into her hands. And now she does change her name. She becomes in her charters ‘Matill marescalla Angliae, comitissa Norfolciae et Warennae.’ I sense a militant gleam in her eyes somehow, and a taking up of tradition that encompassed her ancestors, including her beloved father. She would be a Bigod, she would be a Marshal, but she would not be a de Warenne except in an official capacity of Countess. Professor David Crouch tells us that she was ‘undoubtedly the most powerful and wealthy woman in England from 1242 onwards and that she seems ‘to have conducted herself with a degree of independence during her second marriage. She is found making purchases of land in the Don Valley in Yorkshire in her own right in 1227 when she must have been in residence in the Warenne fortress of Conisbrough.’

Mahelt Marshal died in 1248 and was buried at Tintern Abbey where here bier was borne into the church by her four sons where she was laid to rest with her mother and her brothers Walter and Ancel. Her heart was buried at Lewes Priory, not Thetford where Hugh lies. Was it her wish to have her heart buried at Lewes? Did the children of her second marriage want to keep a part of her close?

I do believe that Mahelt Marshal was a strong, powerful woman who survived and learned wisdom through much adversity. I don’t think she always had it easy. I think she was greatly loved but not necessarily lucky in love.

Although the name of Marshal died out of the history books with the childless demise of William’s five sons, his eldest daughter’s line went on to forge weighty links across the history of the thirteenth century and beyond entering in the bloodlines from which the Stuart Kings of Scotland claimed part of their descent.

Selected historical sources

Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal edited by A.J. Holden with English translation by S. Gregory and historical notes by D. Crouch. Vol 2 Anglo Norman Text Society 2004 ISBN 0 905474 45 7

The Bigod Family: An Investigation into their Lands and Activities 1066-1306 by Susan A.J. Atkin University of Reading P.H.D thesis 1979 Department of History

The Bigod Earls of Norfolk in the Thirteenth Century by Marc Morris, Boydell Press 2005 ISBN 9781843 831648

The Acts and Letters of the Marshal Family: Marshals of England and Earls of Pembroke, 1145-1248 Edited by David Crouch Cambridge University Press 2015