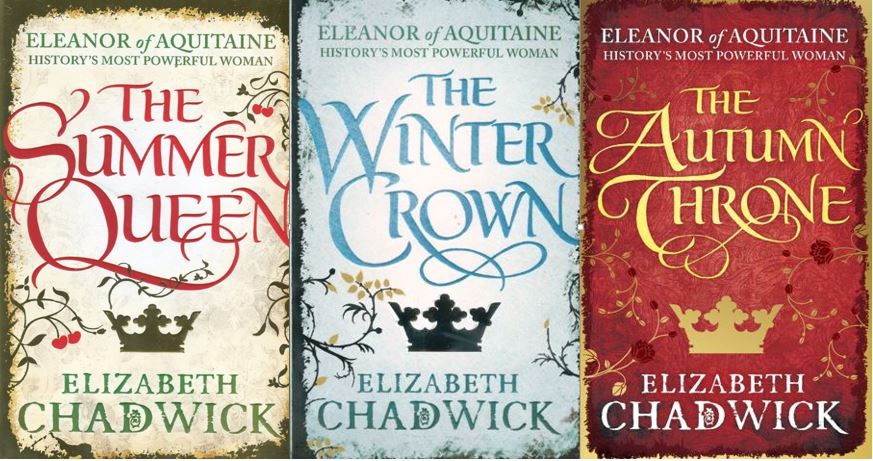

At the Historical Novel Society Conference 1216, I was asked to take part in a panel on Medieval women and their relevance in today’s society. My third novel in my trilogy about Eleanor of Aquitaine, THE AUTUMN THRONE has just been published, and so my given 10 minutes was on Eleanor of Aquitaine.

At the Historical Novel Society Conference 1216, I was asked to take part in a panel on Medieval women and their relevance in today’s society. My third novel in my trilogy about Eleanor of Aquitaine, THE AUTUMN THRONE has just been published, and so my given 10 minutes was on Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Here are my notes.

Writing about the 12th century, you cannot, not come across Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the most iconic European women of that period to modern eyes. Indeed, it was continuously coming across her that piqued my curiosity and made me want to find out more about her and make her the subject of a series of novels. It didn’t matter that she was supposedly well known and that many others had written their take on her down the centuries. Clearly she has been topical for a thousand years and every generation has discovered something about her that resonates.

We find chroniclers blackening her name shortly after her death – in the interests of discrediting the Angevin lineage and then we have the balladeers of the 17th and 18th centuries taking the rumours and gossip and magnifying them in a host of lurid and scurrilous tales that sold like hot cakes on the street corners of the cities and towns. Queen Eleanor’s Confession for example where she supposedly lost her virginity to William Marshal and bore a son by him. Since Alienor would have lost her virginity circa 1137 and William wasn’t born until 1147, it’s a bit of a stretch. But then, just like today – why let the truth get in the way of a good story? Fiction as bestseller trumps fact. No political pun intended with the word “Trump” here – it’s genuinely innocent! The point is that Eleanor, like many women in the public eye has been subjected to all kinds of ‘tabloid’ manipulation down the years. Sometimes of her own volition, but usually not.

Many of the things Eleanor was supposed to have done and which are the lifeblood of our tabloid desire for sex and scandal are either untrue or no more than gossip and rumour. But one can see in their promulgation – such as her supposed affairs with her uncle in her first marriage and with her husband’s father in her second – that gossip was a hazard of celebrity even back then and in Eleanor’s case has been enlarged down the centuries. Both of the above accusations have been run with in popular biographies and novels, but when they are put under the microscope, the edifice crumbles.

What I wanted to do was find my angle on her story. When I write about people it always stems from a general curiosity that then becomes a passion to find out ‘Who were you really? What can you tell me that you haven’t told anyone else before?’ What is hidden under the ‘Beggar’s velvet’ of centuries. Incidentally, ‘Beggar’s Velvet is a term for ‘the light particles of down shaken from a feather-bed and left for a sluttish housemaid to collect.’

When I began researching Eleanor from her popular biographies and from online articles, it became clear that nothing was actually clear beyond the fact that a lot of opinion placed her as a ‘kick-ass’ woman way ahead of her time.’ So many times I have seen people say ‘I really admire Eleanor. I so want to meet her.’ Very plainly she resonates with people powerfully but is being sold today as a woman ahead of her time rather than dwelling IN her time. Professor Michael Evans in his book Inventing Eleanor, which I’ll come to later, says that ‘historians and artists have invented an Eleanor who is very different from the 12th century queen.’

It’s what we think we know versus what is actually known and that beggar’s velvet makes for a very fuzzy outline.

The comments that I kept coming across in popular history interested me because when I began to read the more sober academic content about her, especially the up to date material, it soon became very plain that in fact she was absolutely a woman of the 12th century but that there is a lot of work to be done to open a channel to the mainstream. Rather than being an exceptional rarity, she was on a par with other unmentioned or less lauded women of her era and they were all at it! Empress Matilda, Adela of Blois, Adelaide of Maurienne, and Melisande of Jerusalem for example. All competent women, often fighting the glass ceiling of what was and wasn’t allowed, and is still very much an issue today. They witnessed charters, they saw to daily government of countries and households and were often challenged when trying to take power in their own right. Empress Matilda was called arrogant for refusing to listen to the advice of men. It’s a bit like that Pantene advert today where a man is described as the boss but the women in charge as bossy. Watch here .

Eleanor may have been squashed by both husbands – when you look behind the scenes, the power she wielded was not as great as we tend to want to think – at least not when she was a young wife and mother – authority was to come later, but still she had the diplomatic role of peace-maker and hostess in the social round. She was someone extremely capable of greasing the wheels and making sure that the carts kept rolling along in the background. It’s something that women still do today. They juggle their roles and responsibilities. They are fearsome multi-taskers and Eleanor was all of this. In her second marriage before it hit the rocks, Eleanor was employed by her husband to deputise in their vast dominions and wherever she went, she usually had a couple of their children with her, learning at her side, in their early years, the peripatetic business of the Angevin Empire and the roles they would be theirs or variations of at some point. Her daughters were being educated for later life as queen consorts and duchesses and also mothers to future kings, queens duchesses etc and these were roles they fulfilled very well indeed. So, she was bringing up her children to fulfil expectations and equipping them to do so. Yes, they had wetnurses, but they also had her – apart from John, and we know how that turned out. Even so, as a mother she fought his corner with all the strength she had left in her being. She was a tigress for her children.

Where I tend to think of Eleanor at her most ‘kick-ass’ which is what attracts many of her modern audience is her development as a matriarch and widow once freed from imprisonment after the death of Henry II. I do think she suffered at the hands of two abusive husbands, and the second one in particular was determined to clip her wings, and when she rebelled he put imprisoned her.

She was given control of the ‘Angevin Empire’ while her son Richard the Lionheart was on the 3rd crusade as overall ‘Chairwoman of the board.’ This is the son she had to herself and had educated in Poitiers for a couple of years in the late 1160’s. While sons especially moved out of the maternal household around the age of 7, they still had that maternal influence in those formative years. With Richard in particular, as Eleanor’s heir, she had had more time to further develop her bond with him.

Henry II might have wanted to keep Eleanor under the thumb, but Richard knew and respected his mother’s capabilities and although she had had to endure and struggle throughout her marriages (and again, there are many women who can identify with that today where their role is often viewed as secondary even in a partnership), now she had free rein to rule as she saw fit although in consultation.

One of her first jobs was to bring Richard’s bride from Pamplona in Navarre, to Richard’s winter quarters in Sicily. This entailed a journey by horse (and ship) starting in England and heading down across modern France into Spain. And then, with Berenguela of Navarre, heading over the Alps in midwinter. Eleanor at this stage was 65 years old. Now, I know there are many adventurous retirees around these days, but how many, even the intrepid ones, would tackle something like that. Sure they will board a plane and fly from A to B and get a taxi to the hotel. Yes we globetrot on a regular basis. But to do it on horseback over mountains in adverse winter weather? The sheer guts and energy of the woman are a massive inspiration.

Arriving in Messina in the early spring, Eleanor was warned of trouble at home involving her youngest son Prince John, Count of Mortain who was using Richard’s absence to make mischief and entrench himself in his own power. Eleanor turned her journey around and after just 3 days’ respite was heading back to deal with the situation. She then had to mediate between the brothers – and any mother who has had to deal with sibling rivalry can imagine the difficulties inherent in that one. When Richard was captured on his way home from crusade, she had to put a lid on the unrest in their dominions, sort out a massive ransom, keep everyone talking to each other, and then head to Germany to pay that ransom. She wrote some excoriating letters to the Pope, which although polished by her scribe Peter of Blois bear the ring of truth. She tells the Pope to “Bind the souls of those who hold my son in prison and set him free. Give my son back to me, if you are a man of God and not a man of blood.’

Later on after Richard’s death, once again she had to head out on family diplomatic business which this time meant crossing the Pyrenees in winter to bring another bride in order to solve family political concerns. This time she was asked to go by the new King John, and once again, there was no notion that his mother, now in her late 70’s might be incapable of accomplishing this journey and this mission. And Eleanor too was clearly confident and competent. Indeed, she had a choice of 2 grand daughters and had to select the one she felt was most suitable. So political decision making for the good of the family and putting herself on the line for her family. How many of us do that all the time? Although Eleanor’s would also have been a concern of longer lineage.

Eleanor died and was buried at the Abbey of Fontevraud. She is thought to have had a say in the construction of her own effigy. I think it interesting that she has portrayed herself reading a book – it will be a religious tome, but has her husband and son, lying in regal and more passive state. And since much reading was conducted aloud, it may be that they have to listen to her for eternity! But here we have woman as keeper of wisdom and not silent in death. It is also interesting that on the effigies Henry has no beard but Richard does, which suggests that the greater gravitas might just have been given to the son.

I earlier mentioned professor Michael Evans’s book Inventing Eleanor: The Medieval and Post Medieval Image of Eleanor of Aquitaine published by Bloomsbury Academic. This work nails Eleanor down the ages and teases apart why we think of her as we do. It’s about who she was and who she wasn’t. A lot of our ideas seem to be filtered through the likes of material such as The Lion in Winter and Katherine Hepburn is a particularly enduring image, but while many of those ideas and representations are anachronistic, they still go to show Eleanor’s enduring fascination that has made her the subject of plays and films made and remade a thousand years after her death.

I think Eleanor of Aquitaine was very much a woman of her own time, but that she speaks to us across the centuries. Really it’s not that far away and we are just us as we were then, but with the flotsam of different technology and trends of society floating in our sea. Our interpretations of Eleanor, are of many and varied colours, but I hope (one day) we can all look at her and say ‘I see you.’ And have her look back over her shoulder and reciprocate.