Hamelin FitzCount is one of those supporting role players in English history who is vaguely known to people well versed in the life of the Angevin kings, but otherwise off most people’s radar. However, he has a big part to play in my Eleanor of Aquitaine trilogy, especially in books 2 and 3, THE WINTER CROWN and THE AUTUMN THRONE, as does his wife Isabel, Countess of Surrey and Warenne, from whom he took his title. So who was he? Let’s take a look at what we do and don’t know about him.

The first is a don’t know – his birth date isn’t recorded. His father was Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, the chap in the splendid plaque below. He was husband of the Empress Matilda who was heiress to the Duchy of Normandy and the English crown. (although that right was stolen from her by her cousin Stephen). The marriage took place when Geoffrey was not quite 15 and his bride 26. The union produced 3 sons in the fullness of time but from circumstantial evidence including a separation, does not appear to have been one made in heaven. Geoffrey was known as ‘le Bel’ in his lifetime, meaning ‘The beautiful’ and descriptions say that he was tall, graceful, and long-limbed with red hair and piercing crystal-grey eyes. As well as his legitimate heirs, Geoffrey had an illegitimate son and two daughters by a mistress or possibly mistresses unknown. Some genealogies list the lady as one Adelaide of Angers. There is the very, very scant possibility that she may have been called Matilda the same as Geoffrey’s wife, but in truth, her identity is currently a melange of anyone’s guess.

Whatever the circumstances of their birth, Geoffrey provided for Hamelin, Emma and Mary and took them under his ducal wing. Emma was later to become one of the ladies of Alienor of Aquitaine’s chamber and to marry Welsh prince Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd in the summer of 1174. Mary, became Abbess of Shaftesbury.

Geoffrey le Bel, Count of Anjou, Hamelin’s father. This is his funeral plaque that once lay on his tomb in le Mans Cathedral.

Not a great deal is heard about Hamelin before his marriage in 1164. That he was a longterm part of his half-brother Henry II’s general entourage seems likely. We know he supported Henry at the gathering at Northampton when Archbishop Thomas Becket was summoned to account for his behaviour concerning the matter of land disputes between church and crown (among numerous other things). The proceedings of that council escalated into a slanging match between the Archbishop and the barons. Hamelin got involved, defending Henry’s dignity by shouting at Becket that he was a traitor. Becket’s response to Hamelin was ‘Were I knight instead of a priest, my fist would prove you a liar!’ Later in life, however, after Becket’s death, Hamelin embraced the cult of the murdered Archbishop and claimed to have been cured of blindness in one eye by the cloth covering Becket’s tomb.

Younger sons, minor branches on the family tree and bastards are always dependent on their greater kin for handouts. There is evidence that Henry gave Hamelin lands in Touraine before his marriage, and that he was styled the ‘Vicomte de Touraine’. He later gave his lands at Ballan, Colombiers and Chambray-les-Tours to his nephew King Richard in 1190/91 in exchange for English lands at Thetford. The 3 estates were situated on the Southern fringe of Tours and were in strategic positions on the road to Chinon. This suggests that they were hereditory possessions of the counts of Anjou. The lands were given to Hamelin either by Henry II, or by their father Geoffrey as provision for him.

Hamelin’s greater days, however, came partly as a result of the Becket dispute. Henry’s youngest brother William had been in line to wed the widowed heiress Isabel de Warenne. She had been married to King Stephen’s son William of Boulogne who died in 1159 in Poitou while on battle campaign with Henry II. They had no issue. Becket, on bad terms with Henry II, declared that the proposed match between Isabel and Henry’s brother was consanguineous and refused to permit a dispensation for the couple. William FitzEmpress is supposed to have pined to death on receiving this news. I doubt that very much, but for whatever reason, he died in Rouen a few months after the refusal and Becket was blamed. Henry was not about to let the rich de Warenne lands escape the family clutches, and promptly arranged for Hamelin to marry the widow instead. There was no consanguinity here, and Hamelin was Henry’s sole remaining brother, the other one Geoffrey having shuffled off the mortal coil a few years earlier.

Isabel de Warenne was an heiress worth having. She owned substantial lands in Norfolk, Yorkshire, the south of England and Normandy. At Domesday book, her family’s lands had been valued at £1,140, which put them among the five wealthiest secular holdings in the country after the King. By the second half of the 12th century, the honour of Warenne held over 140 knights fees in England. Isabel’s ancestral holdings included castles at Lewes, Reigate, Sandal and Castle Acre, and would later include the magnificent keep at Conisbrough, inspiration for Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe. Norman prestige lay in the castles of Mortemer and Bellencombre, which were strategic fortresses in upper Normandy and were held in the family by her uncle Reginald de Warenne.

The family were also patrons of Lewes Priory, a Cluniac foundation dedicated to St. Pancras, and Castle Acre Priory in Norfolk. Isabel’s family connections spread far and wide among the Anglo Norman aristocracy. As a note for my personal interest, Isabel’s mother became William Marshal’s aunt by marriage when she wed Patrick Earl of Salisbury as her second husband. Isabel’s great uncle Raoul de Vermandois had been married to Alienor of Aquitaine’s sister. Isabel’s father had died on the 2nd crusade, one of the victims of the massacre while crossing Mount Cadmos. Several birth dates are given for Isabel, but circa 1130 onwards seems the most likely; thus she and Hamelin were of a similar age.

Hamelin and Isabel married in April 1164. In March of that year, a record appears on the Pipe Roll for money for clothes for Isabel – amounting to £4 10s 8d – presumably for her trousseau.

Hamelin took the de Warenne name for his own, adopting his wife’s patrimony and the distinctive chequered de Warenne blazon. Two years after their marriage, he reported to the enquiry of 1166 that he held sixty knight’s fees in Sussex. This was by no means all and it seems that Hamelin was one of an elite handful of Anglo Norman courtiers who were not obliged to report fully on how many knights they could field in battle and to serve the Crown. The de Warenne contribution is missing from the knight’s fee survey documents of Henry II’s time, the Cartae baronum and the Infeudationes militum. However, other sources suggest that the de Warenne estates were in the top 10 of England’s wealthiest and most important honours.

Isabel and Hamelin had four children – a boy and three girls. The boy, William, would go on late in life to marry Mahelt Marshal, eldest daughter of William Marshal as her second husband. The girls all made marriages among the run of the mill aristocracy, but one of their daughters (some sources say Isabel, some Adela) became pregnant by her cousin John Count of Mortain, later King John. They had a son, Richard, who went on to have an effective military career, playing an important role in the Battle of Sandwich in 1217. How much of a scandal this cousinly pregnancy caused at the time, is open to conjecture. It does, however, show a continuing close social link between the families for the opportunity to have presented itself!

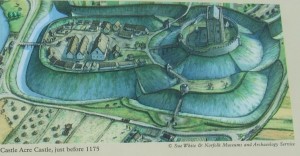

The centres of power in England for Hamelin and Isabel were in Norfolk at Castle Rising, in Lewes at Lewes Castle, and in Yorkshire, at Sandal, and Conisbrough where Hamelin built the magnificent hexagonal keep. It’s thought to be an improved version of the castle built on the de Warenne Norman lands at Mortemer. Perhaps he began building at Conisbrough in earnest following the rebellion of King Henry’s sons and the civil war of 1173. Hamelin sided with his half brother Henry in this dispute, rather than with his impetuous nephews. His loyalty to the crown was always staunch. While his neighbour in Norfolk, Hugh Bigod, took the path to perdition by supporting Henry’s eldest son, Hamelin held firm at Castle Acre – and in all his other territories and ultimately triumphed.

Hamelin doesn’t appear as a signatory to that many charters involved with Henry II, but he was there when it mattered and always quietly efficient in service to his brother. He was present at Fontevraud in 1173 when Henry met with Raymond de St Gilles, count of Toulouse to settle their differences – and thus was also a witness to the start of the Young King’s rebellion against his father. Hamelin attested these charters as ‘Vicomte of the Touraine.’ The Touraine was a politically sensitive area and demonstrates Henry’s trust in Hamelin’s abilities.

Part of the Young King’s rebellion was caused by the fact that his father was negotiating a marriage for John to the daughter of the count of Maurienne. This would have involved John being given the castles of Chinon and Loudon in the Touraine as a marriage portion, castles which the Young king saw firmly as his own. Had the deal gone through, Hamelin would have had custody of those castles until the marriage took place. As it was, it all fell through and turned to rebellion. Hamelin firmly backed his brother Henry II during this time at a point when Henry’s supporters were in short supply.

During the 1180’s Hamelin retired to his own business, much of it concerned with his Yorkshire estates, and he seems to have put his energies into building his wonderful keep at Conisbrough. Historian Thomas.K. Keefe says of him that he “undoubtedly spent more time in Yorkshire than any of the other Warenne earls…” and that “Years of experience at the Angevin court, coupled with private success in the management of the diverse Warenne properties, earned Hamelin a respect that would serve him well in the troubled years following Henry II’s death in 1189.”Hamelin’s next moment in the limelight comes in 1176 when he is found escorting Henry and Eleanor’s youngest daughter to her marriage to King William of Sicily – so a task of status and diplomacy.

Following Henry’s death, Hamelin was present at the coronation of his nephew Richard the Lionheart on the the 3rd of September 1189 and was certainly very busy about the business of the court before Richard departed on crusade. There are 13 charters attested by him before July 1190.In the period leading up to Henry’s death at Chinon, Henry is found at Hamelin’s home manors in Touraine, suggesting that he could rely on Hamelin’s support and loyalty.

As aforementioned, Hamelin exchanged his lands in Touraine for Thetford in Norfolk. This was valued at £35 a year and was an important addition to the de Warenne power base in Norfolk. If the estate made a profit, the moneys had to be handed over to the exchequer, but if it made less than £35, the Crown had to stump up the difference.

While Richard was absent on crusade, Hamelin supported the chancellor William Longchamp against the intrigues of Richard’s younger brother John and also the Bishop of Durham Hugh le Puiset. Perhaps John was persona non grata to him at this time because of the scandal of the illegitimate child he had begotten on Hamelin’s daughter. (my conjecture, no proof). Also Hamelin, rather like William Marshal was a stickler for his word being his bond. Once sworn he was committed. The legend on his seal reads “pro lege, per lege” which translates (roughly) to ‘For the law, by means of the law.’ Since the bishop of Ely, William Longchamp was the law at that point, Hamelin supported him until Longchamp was forced into exile.

In 1193 Hamelin was appointed along with William D’Albini earl of Arundel as one of the treasurers entrusted with collecting Richard’s ransom after the king was taken prisoner on his way home from the Holy Land. On Richard’s return in 1194, Hamelin was granted the privilege of bearing one of the three swords of state at the second coronation, the other two bearers being William King of Scots and Ranulf Earl of Chester. When Richard held a council at Nottingham later that year to deal with the insurgents who had supported John, Hamelin was present at Richard’s side to sit in judgement.

Hamelin was present at John’s coronation on 27th May 1199, and occasionally still attended court duties, witnessing an oath taken by William King of Scots in November 1200. In 1200 too, Hamelin was granted a weekly market at Conisbrough. King John visited Hamelin and Isabel at Conisbrough on the 5th March 1201. In the ensuing years, fences had clearly been mended, and John was not only Hamelin’s king, but his nephew, and father of his grandson!

Notwithstanding, when Hamelin died in May 1202, he was buried at Lewes Priory. Isabel did not long outlive him, dying the following July, and she was buried at his side in the priory choir. I’m pleased about that. So many couples, including William Marshal and Isabelle de Clare were buried far apart in death, but Hamelin and Isabel got to rest together.Hamelin and Isabel were generous patrons to the church. They gave gifts to Lewes Priory, the Hospitallers, St Mary’s York (gifts of fish – bream) , Nostell Priory, the chapel of St. Philip and St. James in the castle of Conisbrough, the priory of St Katherine, Lincoln, (the right of free entry along a causeway belonging to Hamelin for 40 cattle to graze on his moorland) Southwark priory and the abbey of St. Victor-en-Caux. With Isabel and their son William, he was a benefactor of the Abbey of West Dereham and he issued 2 charters to the priory of the Holy Sepulchre Thetford, and several to Castle Acre Priory. In Normandy he was a benefactor of the abbey of Foucarmont. Not that Hamelin was always in full amity with the church. He quarrelled with the Abbot of Cluny over the appointment of the prior of Lewes in 1181, and the dispute continued to rumble on after his death and was pursued by his son.

Studying Hamelin’s charters, I was fascinated to come across the detail that he had had one of them witnessed by a man called Haregrim, who was his goatherd! Now, usually charters are witnessed by men of status and standing in a lord’s life, and they will be listed at the end of charters in order of importance, usually starting with the Church. The charter in question is a gift to Lewes Priory by one Robert Brito. At the end of the charter, the witness list begins with Richard the chaplain of Conisbrough, then several knights, including Hamelin’s chief steward, William Livet. There are clerks in minor orders, Paul and John, then another 4 men of unspecified rank, followed by ‘Haregrimo caperario comitis’ which translates to ‘Haregrim, the earl’s goatherd.’ I like that. It brings the quirky and the idiosyncratic into the story and fuels this writer’s imagination!

Since writing the above, I have come across the detail that ‘caperario’ might also be used in reference to deer, which perhaps makes slightly more sense, but that’s a best guess.

From what I have been able to garner from the scraps available, Hamelin de Warenne illegitimate half-brother of Henry II, was a man of loyalty, steadfastness and integrity. His daily and family life seems to have been a place of measured order, steady growth and contentment – a seaworthy boat from which to weather the violent political storms churned up by his close and royal Angevin relatives whom he served with faith and honour throughout a long and quietly distinguished career.

Select Bibliography:

Early Yorkshire Charters vol 8 The Honour of Warenne Edited by William Farrer and Charles Travis Clay/Cambridge University Press

Dictionary of National Biography – entry by Thomas K. Keefe

England Under the Norman and Angevin Kings volumes 1 and 2 by Kate Norgate

English Heritage links.

Conisbrough Castle