The 14th of May marks the anniversary of the death of William Marshal, who departed this world at noon in the year 1219 at his manor of Caversham near Reading, surrounded by friends in the clergy and his grieving family. It was a sad occasion as all such are, but for William, it was also what was known in the Medieval period as a ‘good end.’ He had had time to make his will and dispose of his wealth as he saw fit. He had settled all of his affairs and made his peace with God, and prepared inasmuch as he could for the afterlife. Unlike many of the men he had served, Henry the Young King, Henry II, Richard the Lionheart and John, he was ending his life in a dignified and peaceful way having lived to a ripe age.

A biographical poem of just under 20,000 lines written in Anglo Norman shortly after his death gives us a moving and full account of the last months of his life. And if William Marshal was an exemplar of how to live one’s life in honour, then his death was a blueprint of how to exit the world.

William Marshal was in his seventy second year or thereabouts, when in the February of 1219 and Regent of England for the underage King Henry III, he became unwell with illness and pain. For all of his life he had enjoyed robust health, so this was an unsettling portent for him. He may have had some indicators before this as he validated fewer acts of government from the November of 1218 onwards. Arriving on horseback at the tower of London he sent for various doctors to attend him, but they told him there was nothing they could do and he was going to die. He took the news stoically and broke it to his son and his household – even trying to comfort them despite his pain. His wife Isabelle was with him at the time and clearly distraught, but determined to give him every support.

William decided that if he was going to die it would be at his favourite and beautiful manor at Caversham on the Thames near Reading, and not in the city of London “which was unhealthy and only added to the great pain he was in. His view was that he could more easily put up with his affliction on his own ground: if in the nature of things, death was to be his lot, he preferred to die at home than elsewhere.”

Red pin point indicates the position of Caversham relative to Reading, Windsor and London

William and Isabelle were rowed up the Thames to Caversham. Their journey was smooth and untroubled, and he settled in to the home where he was to die. Once there, he asked those who were governing the country on behalf of the young king Henry III, to come to him so that he could officially hand over the reins. They all gathered at his bedside, including the young king and the papal legate. William informed the 11 year old Henry III that he could no longer serve him because he was dying and others needed to take over. There was some squabbling about who should have this role, but William was still strong enough to push through the quarrel and settle the matter to the obedience, if not entire satisfaction of all those present. Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester had to be put in his place, It was also at this time that William warned the young Henry III that if he were to follow in the footsteps of a certain ‘wicked ancestor’ then he wished him a speedy death. Here, at his own dying, we get the truth about what William Marshal really felt about King John.

The famous ‘Scarlet Lion’

The matter attended to and the burden of government relinquished, William turned his thoughts to making his will, providing futures and guidance for his children, and then to spiritual matters. At first, he was going to leave his youngest son Ancel, still a child, to make his own way in the world as a knight errant when he grew up, but he was persuaded by his former squire and now close friend and adviser John of Earley to give Ancel land worth £140 to support himself. This may of course have been a literary device to show how William’s men had an influence on him when it came to giving advice. William was also concerned about his youngest daughter Joanna because he had not yet arranged her marriage, but he settled some money and land on her too.

His immediate family affairs sorted, William asked John of Earley to go to Stephen D’Evereux in Netherwent, Wales, and bring him to him the lengths of silk cloth that he had been keeping in store there. It was a long journey and John rode hard, “travelling far greater distances each day than is usual’ returning with the cloths as fast as he could.

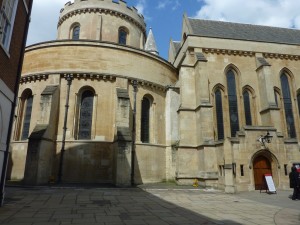

When he presented the cloth, at first people thought it was a little faded, but when it was opened out it was discovered to be “very fine and valuable choice cloth of good workmanship.” William had had these two pieces for 30 years. He had brought them back from the Holy Land with him and had always intended them to be used for the purpose of draping over his body when he was laid in the ground. They were to be his shroud. At this point he told everyone that he wished to be buried at the Temple church. He told those around him that “When I was away in the holy land, I gave my body to be buried by the Templars at the time of my death, in whatever place I happened to die. That is my wish, that is where I shall be laid to rest.’ He also told them that if the weather was bad, they were to buy lengths of coarse grey cloth (known as burel) with which to cover the silk so that it would not become damaged or dirtied by damp weather. The grey cloth was then to be given in charity. His instructions caused those around him, including his son to “weep pitifully.” Seeing the pain he was in, his eldest son gave instructions that his father was to have a constant guard around him. Someone was to be with him always. Relays of three knights would keep vigil at all times. As well as the knights there were other youths and gentlemen to help out – one supposes to take care of William’s bodily functions. His son said that he would take the night watch together with John of Earley and Thomas Basset.

Temple Church interior

Taking Templar vows meant that he could no longer have any physical contact with women. The Earl, who was generous, gentle and kind towards his wife the Countess, said to her: ‘fair lady, kiss me now, for you will never be able to do it again.’ Isabelle was distraught, and both she and William wept as they kissed and said a final farewell to embraces of any kind.Letters were sent to the Templars. William’s will was witnessed and sent to executors including the bishops of Winchester and Salisbury. Aimery de Saint-Maur, master of the Templars in England arrived at Caversham to see William. Aimery de St. Maur was a close friend to the Marshal. William announced to his family that it had been some time since he had pledged himself to the Temple, and now he wished to become a monk in the order. He told Geoffrey his almoner to go to the wardrobe and bring a cloak from it. It was a Templar cloak that he had had made more than a year ago and had kept in his possession without telling anyone (rather like the shrouds).

Shortly after William had taken his Templar vows, Aimery de Saint Maur departed back to London, but died there soon after arriving. William was not told of his death in case it aggravated his condition, but the outcome was that he and Aimery would be laid side-by-side in the church, companions in death as they had been in life.

William’s own condition deteriorated to the point where he could no longer eat or drink beyond a few mushrooms. His men even tried rubbing white bread crumbs in his hand but that didn’t work. To all intents and purposes William had stopped eating. Even so it was to be another fortnight before he died. During this time of suffering he had a discussion with one of his men, Henry FitzGerold, The latter was concerned that the Marshal might not be granted a place in heaven because of all the tourney prizes and wealth he had won. The Marshal was having none of this and said that the church shaved people to closely. He had taken the ransoms of 500 knights and kept their arms, horses and all their equipment. He couldn’t do anything about it now, and if that was the case then no man could find salvation.

At this time, William’s daughters visited him.Everyone else was in the room, including the Marshal’s son, William, who was sitting in front of his bed. William said that he wanted to tell them all a surprising thing. John of Earley said he would like to hear it, providing it was not going to wear the Marshal out. William then said that he had a great urge to sing, an urge he had not had in three years. When John said that he should do so and it would be good for him, William told him to be quiet because everyone would think he was a madman, and he refused to sing. So John said it would be a good idea if William’s daughters sang to him, (I like John. I can imagine him thinking of ways round the problem of getting a dying man perhaps slightly querulous with pain to do what he really wants but is holding back). The daughters rose to the task magnificently, especially Matilda even though she was distraught at her father’s condition. When it came to little Joanna’s turn she was shy, and now William, who had loved music all his life, found a spark. He told her not to be bashful when she sang because she would not perform well. “Don’t be bashful when you sing, for if you are, you will not perform well and the words will not come across in the right way.” And then he taught her how to sing by doing so himself. This to me says more than anything how much William loved music, how important it was to him, that he would sing on his deathbed even when in great pain. And he still cared enough to want it to be done right!

William continued to make plans for his funeral in his last days. He instructed his son to stay close to his corpse on the road so that he could distribute alms to the poor, and to give food and drink, clothes and shoes to a hundred of the poor in William’s name.

William’s friend the Abbot of Notely arrived to give succour to William and tell him that his brethren were praying for him, and William promised the Abbot’s order money from his will. William was still aware enough and lively enough to tell off one of his own clerks. William had had made some garments for his knights to give as gifts. John of Earley asked what he should do with the ones that were upstairs with their fur trimmings because no one had mentioned them. The clerk Philip suggested that they could be sold to deliver William of his sins. William told him to hold his tongue, that he’d had enough of his bad advice, and that his knights would have their robes at Whitsuntide. It was the last time he would ever be able to give them robes, even posthumously, and he wasn’t having some upstart clerk tell him what to do. He immediately ordered John of Earley to distribute the robes and if there weren’t enough to go around to obtain more from the warehouse in London.

While the family were trying to get William to eat something, he told them that he had had a vision. He had seen two men in white, one on his right, one on his left. The feeling was that these were two angels who had arrived to show William the right path, although no one was quite sure and John of Earley said he always regretted not asking William more about them.

On the Tuesday before Ascension Day, at midday, William Marshal died. His family had thought him sleeping, but when his son William came to speak to him, he found him in his last moments of life. John of Earley did his best to revive him with rosewater, but it was plain that William was beyond that. The doors and windows were flung open and the household hastily assembled, everyone rushing to the room including Countess Isabelle. A cross was placed in William’s hands, and he died, surrounded by his family and household on a green spring morning. The first thought is that it is not a good time to die in the heart of a beautiful English spring, but perhaps, really, it is the perfect moment.

William’s body was prepared and mass was sung with him in his own personal chapel at Caversham. Isabelle was so distraught that she could barely hold herself together during the singing of the mass.William’s body was then taken to rest in Reading Abbey, then to Staines. Along the way the funeral cortege was met by the Earl of Warrene and the Earl of Essex, the Earl of Oxford, the Earl of Gloucester and many others.William was borne to the Temple church where a candlelit vigil was ordered by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton.

Temple Church exterior

“The Archbishop ordered the vigil to commence and. as was right, the vigil around the body was accompanied by a magnificent display of candles and a magnificent service, well sung and well read, and there were clerics singing psalms whose efforts were not wasted.”

The following day the funeral was held and Stephen Langton received great praise for his eloquence and the finesse of his words. William was buried as he had wished in front of the cross beside his friend Aimery de Saint Maur.

“When the body was on the point of being interred, the archbishop said ‘See, my lords, how it is with this life: when each and every one of us comes to his end, there is no sense to be found in us, for we are then nothing but so much earth. Look there, see, the best knight to be found in all the world in our times. And in God’s name what will you say then? All of us must come to this, it is an inescapable fact that each of us must die when his day comes. Just look at this exemplar here, ours as well as yours. Let each man say the Lord’s Prayer, entreating God to receive this Christian soul into his realms in heaven, to sit in glory alongside his own, for we believe this man to have been a good man.”

Today, almost 800 years since William Marshal’s death the lines of the Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal tell the incredibly moving story of William Marshal’s final fight that ended not in defeat but in an embracing humility and acceptance. The subject matter is one man’s dying, but I am never depressed when I read it. It may bring me to tears, but I am always exalted and uplifted and determined to live my life in better ways.

Hail William Marshal, but not farewell.

Paying my respects