ON THE ANNIVERSARY OF WILLIAM MARSHAL. Died 14th of May 1219. Author’s photograph.

ON THE ANNIVERSARY OF WILLIAM MARSHAL. Died 14th of May 1219. Author’s photograph.

My novel TEMPLAR SILKS, covers the story of William Marshal’s experiences in the Holy Land when he went on pilgrimage, setting out in the late summer of 1183, and returning to Normandy in early 1186. The title is a reference to the two pieces of silk that William Marshal brought home from Jerusalem, intended for use as his burial shrouds when the time came. Those shrouds are pivotal to my story which is structured around the circumstances of how William came to obtain them and what role they played in his life.

William’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land was in fulfillment of a vow he had made to his lord, Henry the Young King, son of King Henry II. The Young King had sworn to go on pilgrimage, but died of dysentery while rebelling against his father. On his deathbed, he entreated William to take his cloak to Jerusalem and lay it at the tomb of Christ in atonement for his sins (not least I suspect the robbing of several shrines that coincided with him contracting the dysentery that killed him). William, who had his own sins to atone for, including collusion in the shrine robbing, pledged to take the road to Jerusalem and do as his dying young lord requested.

The only reference to William’s burial shrouds comes from The Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal – The History Of William The Marshal, a work commissioned by his eldest son and completed by a French scribe called John by 1226. It tells the Marshal’s life story in rhyming lines from cradle to grave, although some sections are more detailed than others, and often the truth is embellished to add a shine to William’s deeds or skimmed over when those deeds are not especially edifying, or perhaps even detrimental to its hero. Nevertheless there is a strong core of truth in the narrative and many parts can be corroborated from other historical records.

The Histoire is a work of over 19,000 lines, but only 28 of those lines specifically mention William’s time in the Holy Land, and even that mention is glossed over and inaccurate. We are only told that the Marshal ‘performed so many feats of bravery and valour, so many fine deeds that no man before had performed so many, even if he had lived there for seven years.’ The chronicler then admits that he has no idea what these deeds were because he wasn’t there, didn’t witness any of them and couldn’t find anyone to tell him what they were – he only knew they were very weighty.

Having performed his deeds and obtained his shrouds – more about them in a moment – William set out for home. The Histoire tells us he took his leave of King Guy, his knights, the Templars and Hospitallers, none of whom wanted him to leave because of his fine qualities. The problem with this is that when William left the Holy Land, Guy de Lusignan (who had been his enemy in Poitou) was not King. We know William was home by February 1186, and Guy did not become King of Jerusalem until the autumn of that year. There is some fudging going on – either down to lack of information or because what happens in the Holy Land stays in the Holy Land. The author of the Histoire continues his theme of ignorance by saying he knows nothing of the journey home, he knows no one who can tell him, and ‘it is foolish to devote effort to something that is none of my concern.’ However, he does inform us that William found King Henry II at Lyons la Foret with the court – and we know from other sources that Henry II was there in February 1186.

The shrouds themselves are mentioned towards the end of the Histoire, when William requests them to be brought to his deathbed at his manor of Caversham near Reading. He asks one of his most trusted friends, his former squire and ward John D’Earley, to go on a mission to Wales (very likely to Chepstow Castle) to see to some business there.

This is the piece in translation from the Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal.

” On your return from this mission, bring me the two lengths of silk cloth which I gave to Stephen to look after; a man who makes provision in advance does well. And whatever happens to you, make all haste to return here.’

John D’Earley duly departs on his mission and returns with all speed with what William has asked for.

“Here are your lengths of silk, my Lord, which I was instructed to bring to you.’

When he heard this, he took them, And he said to Henry FitzGerold: ‘Henry, look at this fine cloth here!’

‘Indeed my Lord, But I can tell you that I find them a little faded unless my eyesight is blurred.’

The Earl replied: ‘Unfold them, so that we might be in a better position to judge.’

And once the lengths of cloth had been unfolded, they looked very fine and valuable, choice cloth of good workmanship… He shows them to his son and his knights, saying: ‘My Lords, just look here! I’ve had these lengths of cloth for 30 years; I had them brought back with me when I returned from the Holy Land, to be used for the purpose which they will now serve; my intention has always been that they will be draped over my body when I am laid in the Earth; that was the destination I had in mind for them.’ … ‘My dear son,’ he said, ‘I shall tell you, without a word of a lie: when I was away in the Holy Land, I gave my body to be buried by the Templars at the time of my death, in whatever place I happened to die. That is my wish, that is where I shall be laid to rest.’

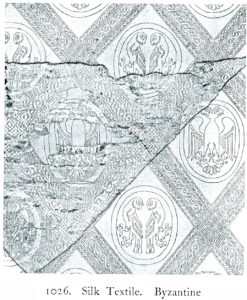

Black and white plate of white silk fabric from the V&A collection of Medieval woven fabrics. 11th century.

A few lines later he says:

‘John… take these lengths of cloth here. When I am dead, cover me with them, and cover and surround the bier in which I am carried. And there is another instruction I wish to give you: if there is snow and bad weather, go and buy lengths of burel (coarse grey cloth), I don’t mind which, attractive or otherwise, and cover the silk with them, so that it is not damaged or dirtied by the damp weather. And after I’m buried, give the cloth there, to the brothers and they will do with it as they wish.’

After this, William prepares to take the full vows of a Templar monk and he says ‘It is some time since I pledged myself to the Temple, and now I wish to become a monk in it.’

What we learn from all this is that while in the Holy Land William obtained his own finely worked silk burial shrouds and that they sufficiently important and precious for him to keep until it came time for him to die. Clearly too, he made some kind of undertaking with the Templars and intended to be buried as one of them at the end of his life – be that sooner or later. Professor David Crouch, senior authority on the Marshal believes that William must have felt that his life was in serious peril at some point during his Holy Land experiences, and that he made his will here and that it involved the Templars. I believe it is absolutely no coincidence that the revealing of the shrouds to his eldest son and his inner circle of knights immediately precedes the information that he desires to be buried by the Templars. I also believe that these pieces of silk are his covenant with the order – a symbol of the pledge he had taken. We are never told that he bought them, ( although you may come across that statement in a couple of his biographies). The phrasing in the Histoire, I am told by a historian, may refer to a bargain or barter, in which case if the shrouds are in token of a pledge it makes total sense.

A year before he was ordained into the Templars on his deathbed, William had had a Templar mantle made and kept it just as well hidden as the silk shrouds, even if for much less time. The mantle was a symbol of his entry into the Templar order and a farewell to all things secular. The silk shrouds were his farewell to the world, displayed as he was borne to his grave (unless bad weather intervened) and then used to embrace his body within his tomb in the Temple Church. Even stored away for thirty years, those lengths of silk were extremely important to William. Perhaps a reminder of his pledge to the Templars, and perhaps as a form of pre-death comfort and security in the days of his last battle.

What did the shrouds look like? We do not know, only that the two pieces were of very fine and choice cloth, sufficient to cover William’s body and his bier. We don’t know if they were patterned or coloured. Even the fact that one of William’s men felt they were a ‘little faded’ does not determine their appearance. If vibrant they might have faded, and if pale, they might have shown stains in the creases from being folded for so long.

There is a very famous white silk that was made in the Christian held city of Tyre in William’s time. Known as Tafeth it was white and ‘exported thence to all parts, being extremely fine and well woven beyond compare. The price is also very high and in but few of the neighbouring countries do they make as good a stuff.’ (William of Tyre). Some white silks were woven with a pattern such as the one in the first illustration which is 11th century Byzantine and is in the V&A catalogue of early medieval textiles. The black and white photo print is from the 1920’s and doesn’t do the fabric justice. But imagine a silvery white pattern shining on a pale background. Or the shrouds may have been multi-coloured. This is an image of a bier shrouded in decorated cloth from the Maciejowski Bible.

I do find it fascinating that William Marshal set out with a brief to take his young lord’s cloak to the Holy Land. He had a sacred pledge to fulfill and the cloak, stitched with its pilgrim cross on his outward journey, was a symbol of his intent, to be protected with his life and honour. Coming home, he returned with another bundle of portentous cloth and another vow unto death. A circle completed.

You can read the opening to TEMPLAR SILKS by clicking here: TEMPLAR SILKS extract

Quotes are from History of William Marshal, edited by A.J. Holden with English translation by S. Gregory and historical notes by David Crouch. Published by the Anglo Norman Text Society.

For anyone wanting to read more about William Marshal, I highly recommend David Crouch’s biography in the 3rd edition

You can also read my blog post on William Marshal’s pilgrimage here. What Happens in the Holy Land Stays in the Holy Land