Introduction

Introduction

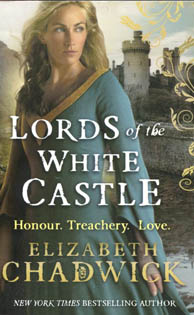

Lords of The White Castle is a novel based on a remarkable true story of honour, treachery and love spanning the turbulent reigns of four great Medieval kings. Award winning author Elizabeth Chadwick brings the thirteenth century vividly to life in the tale of Fulke FitzWarin. From inexperienced young courtier to powerful Marcher lord, from loyal knight to dangerous outlaw, from lover of many women to faithful husband, Fulke’s life story bursts across the page in authentic detail.

A violent quarrel with Prince John, later King John, disrupts Fulke’s life ambition to become ‘Lord of the White Castle’ and leads him to rebel. There are perilous chases through autumn woods, ambushes and battles of wit as Fulke thwarts John at every turn. No less dramatic is the dangerous love that Fulke harbours for Maude Walter, a wealthy widow whom John wants for himself.

Negotiating a maze of deceit, treachery and shifting political alliances Fulke’s striving is rewarded, but success is precarious. Personal tragedy follows the turbulence of the Magna Carta rebellion, culminating in the destruction of everything for which Fulke has fought. Yet even among the ashes, he finds a reason to begin anew.

EXTRACT

To set the scene: Fulke FitzWarin has rebelled against King John. During a skirmish Fulke is wounded by a crossbow bolt and seeks succour at the manor of Higford, belonging to his paternal aunt. Maud Walter, a friend’s wife to whom Fulke is attracted, is on her way to join her husband when she too arrives at Higford, and the scene is set for confrontation….

Rounding another turn, she came upon the manor. Lulled by the scenes of pleasant industry in the village, she was startled to find the place frenetic with activity as if someone had thrust their arm into a hive of bees. The courtyard was filled with horses and armed men, recently arrived to judge by the chaos. Emmeline’s grooms were busy amongst them and the knights themselves were unsaddling their mounts. Maude felt a selfish rush of dismay and irritation, swiftly followed by a burst of curiosity.

“Shall I find out what is happening my lady?” asked Wimarc of Amounderness who was in charge of her escort.

Maude nodded. “Do so.”

Wimarc dismounted and went to speak to the men within. Maude watched him join a group, saw him listen and nod. Glancing beyond, she saw two young men in conversation, one as tall and thin as a jousting lance, the other smaller and stockier with a head of cropped red curls. Philip and Alain FitzWarin. And where Philip and Alain went, Fulke was likely to be ahead of them. She scanned the crowd, her stomach suddenly turning like the mill wheel.

Wimarc returned and told her what she already knew. “Lady Emmeline’s nephews are here to rest up for a short while,” he said. He gave her a shrewd look. “Do you want to ride on my lady?”

Usually decisive, Maude did not give him an answer straight away, but looked at the activity in the courtyard and gnawed her lip. It would be for the best she thought. Accommodation would be horrendously crowded and the thought of seeing Fulke made the wheel in her stomach churn and surge. The thought of not seeing him filled her with flat disappointment. She had promised Emmeline that she would return this way and she owed Fulke the courtesy telling him how sorry she was for his mother’s death. But with so many men, his purpose was obviously not just to visit his aunt and pay respects at his mother’s grave.

Wimarc rubbed his palm over his bearded jaw and as if reading her thoughts said, “They tried to lay an ambush for Morys FitzRoger and lord Fulke came away from it with a crossbow bolt in his leg. Lady Emmeline’s tending him now.”

“A crossbow bolt?” Maude stared at Wimarc in horror. King Richard had died of a crossbow bolt in the shoulder – a minor battle wound that had festered and poisoned his blood so that a week later he died in agony. “Lady Emmeline will need aid if she is to tend Lord Fulke and see to all these men,” she said, her decisiveness returning. Gathering the reins, she nudged Doucette through the gateway into the frantic activity of the yard.

Maude quietly parted the thick woollen curtain and entered Emmeline’s bedchamber. It was a large, well appointed room at the top of the manor with lime-washed walls that had been warmed and decorated by colourful hangings.

Fulke was in Emmeline’s bed, propped up against a collection of bolsters. There were dark circles beneath his eyes, his mouth was thin with pain and weariness, and the bladed bridge of his nose had caught the sun so that he looked more hawkish than ever. Although battle-worn, he scarcely appeared to be at death’s door and the fist of fear beneath Maude’s ribs, ceased to clench quite so hard.

The covers were flapped back and Emmeline was leaning over his lower body, her own complexion the colour of whey. As Maude advanced to the bed, Fulke looked up. Alarm flickered in his eyes and he lashed the covers back over himself so swiftly that he almost took out his aunt’s eye on the corner of a sheet.

“What are you doing here?” he snarled in a voice that was as far from the grave as Maude had ever heard. “Get out!”

Hand over her eye, Emmeline turned. “Maude?” Behind the half-mask of her fingers, a look of relief swept over her face.

“I said I would return this way.” Maude looked angrily at Fulke. His rejection made her all the more determined to stand her ground. “With an invalid to nurse,” here a disparaging curl of her lip at Fulke, “and a passel of hungry men to feed, you are in need of help.”

Emmeline rose and wiped her streaming eye on her cuff. “Bless you child,” she said in a heartfelt voice.

“What do you want me to do?”

“You’re not going to do anything,” Fulke snapped, drawing himself up on the bolsters and glowering furiously. “I’m a dangerous rebel, and if you so much as associate with me, you’ll be tainted too.”

Maude shrugged. “Who’s to know?” she said. “Theo would be more angry with me for riding away than for staying to help.”

Emmeline looked uncertainly between them. “It is true that I will be very glad for you to stay, but not if it is going to put you in danger.”

“No more danger than you are in yourself,” Maude said to the older woman. “My brother-in-law is the Archbishop of Canterbury and the King’s Chancellor. That surely must bestow some protection.”

“His support never did us any good,” Fulke growled.

Emmeline turned round, her sallow cheeks flushing. “Has your wound bled the courtesy from your body?” she demanded. “What is wrong with you that you should behave like a thwarted small child?”

“Aren’t all men like that when they are injured?” Maude gave Emmeline a wry, woman to woman smile.

Emmeline snorted down her nose. “Some of them are like it all the time,” she said darkly.

Clearly annoyed, but recognising that a retort would only lead to more ridicule, Fulke clamped his jaw and thrust his spine against the bolsters. “If you can remove this arrow from my leg, I won’t trouble your hospitality above a couple of days,” he said.

“I’ve sent for the priest. He’ll be here as soon as he can.”

“The priest?” Maude thought of the agitated note in Emmeline’s voice and linked it with her pallor as she leaned over Fulke’s wound.

Her horror must have shown on her face because for the first time since she had entered the room, Fulke smiled, albeit savagely and without humour. “You need not concern yourself, Lady Walter, I am not about to be administered the last rites.”

“I…”

“Someone has to cut this arrow out of my leg. Having seen the mess William makes gutting a hare, I don’t trust him to do the deed, and I won’t ask any of the men. It’s too great a responsibility. If aught should go wrong, I do not want one of them to carry an unnecessary burden of guilt.”

The speech had begun with defensive, sardonic humour, and ended in sincerity. Maude’s throat tightened as she was yielded a glimpse behind his shield.

“I am afraid I cannot play the healer’s part,” Emmeline said, unconsciously wringing her hands. “Even the sight of blood makes me faint. My father always said that it was a good thing that I wasn’t born male.”

“And can the priest?”

Emmeline nodded, although there was a spark of doubt in her eyes. “He set Alwin Shepherd’s broken arm last year and it has healed cleanly.

“But he has never removed an arrow?”

Emmeline shook her head. “Not that I’m aware,” she said.

Maude pushed up her sleeves, exposing slender forearms, and advanced to the bed. “How deep is it in?”

His fist clenched on the bedclothes holding them firmly down over his leg and in his face, there was fear, anger, and stubborn mutiny. Maude looked at him and then down at his hand, remembering how the sight of it had affected her as Theobald’s new bride. Now the long fingers were curled in tight and the raised knuckles were bleached.

“Let me see,” she said, laying hold of the sheet’s edge.

“Why?” he challenged. “I warrant you have never removed an arrow from flesh either.”

“No,” Maude admitted, “but I have seen it done. One of Theo’s knights received a quarrel in the leg during a hunt, and we were fortunate enough to have a Salerno trained chirugeon claiming hospitality in Lancaster at the time.” She held Fulke’s gaze steadily. “Me, or the priest. The choice is yours.”

He returned her stare, then with a sigh capitulated, raising his hand and looking away. “Do as you will.”

Maude lifted the covers and folded them aside. He wore a loincloth for modesty, but still she had never been as close to any man’s intimate area save Theobald’s. Fulke’s thighs were long, powerful, and surprisingly hairless given his dark colouring. On the nearside one, the stump of a crossbow bolt protruded from the skin like the stalk of a pear. The full length of the shaft had been snapped off to leave about two inches standing proud.

“I’ll need a thin wedge of wood,” Maude murmured as she gently prodded and felt Fulke tense like a wound bow.

“I don’t need anything to bite on,” he said indignantly.

“Oh stop being so proud, you fool,” Maude snapped. “And it’s not for you to bite on anyway. The way you’re behaving it might be a good thing if you used your own tongue as a clamp.” She raised her head to Emmeline and gestured with forefinger and thumb. “A wedge of wood about this thickness, no more. I’ll also need two wide goose quills, a small sharp knife and needle and needle and thread.”

Emmeline nodded and turned away.

“Oh, and in my baggage there’s a small leather costrel. Ask my maid to find it.”

Fulke’s aunt vanished on her errand.

Maude sat down at the bedside. One half of her mind was studying the other half in astonishment. Had she really given orders so briskly and with such confidence of knowledge? Any moment now the façade would desert her and leave a trembling wreck, no more capable than Emmeline of doing what had to be done.

“I am sorry that your mother has died,” she murmured. “I came to see her at Alberbury when she was ailing and I stayed with her.”

Fulke stared obdurately at the wall hangings directly opposite his line of vision. “That was kind of you,” he said stiffly as if the words were being forced out of him. “My aunt did tell me.”

Maude pleated the coverlet in her fingers. “We became good friends,” she said. Some instinct held her back from telling him how close. She did not think he would want to hear that Hawise considered her the daughter she had never had. At least not now, when it might seem like a rejection of the sons she had borne.

“Did she suffer?”

Maude busied herself with the coverlet. “No. At the end she went peacefully in her sleep.”

“You’re not a very good liar, are you?” He turned his head so that their eyes met on the level instead of from a side-glance.

“What do you want me to say?” Maude demanded. “Will it make any difference to know that she was in terrible pain? Will it ease you to know that she only died in her sleep because we dosed her with Alberbury’s entire supply of poppy syrup to calm her agony?” She blinked and scrubbed angrily at her lashes. “I loved her, and I didn’t want her to go, but for her own sake I prayed harder than I have ever done in my life for God in his mercy to take her.”

There was a quivering silence. Then she saw his throat work and the betraying glitter in his own eyes. He turned his head again, this time looking away, and muttered indistinctly beneath his breath. Of its own volition, her hand crept from its pleating, to cover his on the bedclothes. Even while she made the move in compassion and the need to offer comfort and be comforted, a part of her mind acknowledged that it was something she had wanted to do ever since her wedding breakfast.

He tensed, his face remained averted, but he did not withdraw from the light pressure.

The curtain rattled on its pole as Emmeline returned with Barbette in tow and the requested articles. Resisting the impulse born of guilt to snatch her hand away Maude tightened her grip.

“How good are you at ignoring pain?” she asked Fulke.

He shrugged and looked at her, his expression restored to one of sardonic humour. “That is hard to say since I have never had an arrow taken from my flesh before. How much are you going to inflict?”

Maude briefly compressed her lips while she pondered how to reply, finally deciding that in kind was as good a way as any. “That is hard to say also, since I have never taken an arrow from anyone’s flesh before.”

Fulke eyed her fingers upon his. “Then we are well matched,” he said.

Maude reddened. “In this matter, yes,” she said, trying to appear unruffled and in her own tim removed her hand.

“Do you want me to stay?”

Maude glanced over her shoulder. Emmeline’s voice had been pallid with fear. “No, there is nothing you can do, but if you could send two of the men in, I would be grateful.”

Emmeline nodded and scurried out, her relief obvious.

“Two men?” Fulke raised his brow. “You think it is going to be that difficult to hold me down?”

“You may well buck like a branded colt, and do serious damage to yourself.”

She took the knife, examined its edge and then going to the brazier burning in the middle of the room, thrust the instrument among the glowing lumps of charcoal. Fulke stared, and she saw sweat spring on his brow. She had no doubt that if he had been sound in limb he would have run from the room.

“Good Christ, woman, what do you think you’re doing?”

“The chirugeon who showed me his art said that fire purifies. To stop a wound from festering you must use instruments that have been tempered in its heat. Don’t worry; I’ll quench it first.”

“I think I need to be drunk,” he said weakly.

Maude gave a brisk nod. “It would be a good idea.” Leaving the knife in the glowing charcoal, she went to the costrel and removed the stopper. “Are you familiar with uisge beatha?”

Fulke nodded, pulling a face at the same time. “I was introduced to it as a squire in Ireland with Theobald – vile stuff, but useful if you crave to get drunk without bursting your bladder.” He held out his hand for the costrel. Before she gave it to him, Maude poured off some of the almost colourless liquor into a large pottery beaker.

“Are you going to drink that before or after you cut out the arrow?”

“Neither,” she said. He was jesting, trying to be light and flippant, but she knew that he must be feeling sick with apprehension and fear. Even if the operation of removing the arrowhead was simple, it was still no small undertaking and she knew without a doubt that for a brief time at least he was going to be in agony.

The curtain pole rattled again as two of Fulke’s brothers entered. Not William, who was nursing cracked ribs and heavy bruises, but Ivo and Richard who were both big and strong. The latter was cramming the last of a griddle scone into his mouth and dusting his hands on his tunic.

“Is there ever a time when you’re not eating?” Fulke demanded from the bed.

Richard patted his solid stomach. “Extra flesh acts like another layer on your gambeson,” he said.

“It’s no wonder your horse sags in the middle.” Fulke took a swig from the costrel, and his repartee was immediately silenced by a glottal wheeze.

Maude waited until he had drunk more than half the remaining uisge beatha in the costrel then gestured Ivo and Richard into position. Fetching the razor, she quenched it in a jar of water standing nearby and then with a prayer on her lips picked up the mead cup and sloshed some of its contents over Fulke’s wounded thigh.

Despite being well on the way to gilded, Fulke still arched and yowled like a scalded cat and there was nothing his brothers could do to hold him. “Bitch!” he gasped. “Vixen, bitch!” He fell back onto the bed, his lids squeezed tightly shut and moisture leaking out between them.

“That is the worst over,” Maude said tremulously. Her heart was pounding in her throat, at both Fulke’s reaction and what she was about to do.

His voice was ragged. “Christ, just do what you must, and be quick about it!”

Faces grim, Ivo and Richard pinned him. Maude took the knife. “I have to open the wound to reach the arrow head. With good fortune it will not be barbed and can be eased out.”

“And if it is barbed?” Ivo gave her a searching look from beneath his brows.

“That is what the goose quills are for. They are set over the tines so that when the arrow head is drawn out, the flesh is not ripped.”

Both brothers winced. Fulke made an inarticulate sound conveying drunken, angry impatience.

Maude took a deep breath, entreated God to steady her hand, and set to work. To his credit, Fulke tried hard not to tense his leg and she was able to cut down to the arrowhead reasonably quickly. There was plenty of superficial blood, but she could tell from the way it welled around the wound that no major vessel was involved. A gentle probe revealed that mercifully the bolt head was not barbed. She took the thin wedge of wood, slid it carefully into the side of the slit and eased the iron arrow out.

“Here,” she said, presenting it to Fulke in her bloody fingers. “A talisman for luck.”

“Luck!” he laughed weakly. His complexion was ashen and his pupils huge and dark with pain. “What kind of luck is that?”

“The kind that lets you off lightly. It was only in your flesh, no damage to bone or major vessels. If you do not suffer the wound fever or stiffening sickness, you will live with naught but a scar to show for it.”

While he was still looking at the bloodied bolt, she removed the wedge and doused the wound in uisge beatha a second time. Once again he reacted like a scalded cat, this time, almost losing consciousness. Maude quickly packed the wound with a greased bandage and then wrapped it in strips of linen swaddling band.

“How long before he is able to ride again?” Ivo asked. His look was a little reproachful and she could tell that he thought her unnecessarily cruel. “When can we leave?”

“A week at least, but better two. You’ll need to do some hunting for your suppers if you are not to strip Higford of its supplies.”

“Oh yes, we’ll hunt,” Ivo said. The way he looked at Richard made Maude decide not to ask the kind of prey they had in mind, although she suspected that any royal manors within the vicinity might soon find themselves receiving a visit. So she merely nodded and changed the subject.

“He needs peace and quiet to sleep and recover,” she murmured. “One of you can sit with him and make sure he needs for nothing. I will speak to your aunt – reassure her that all is well.” She grimaced at the dried blood caking her fingers. “Although I had best wash my hands first, or she will never believe me!”

That raised half-smiles from Fulke’s brothers. She took the costrel bottle and swigged down the dregs. The fire of the brew hit the back of her throat and shot in a line of liquid flame to her belly. She gasped, first with shock, then with relief. Fulke half-opened his eyes and looked at her mazily. “I don’t know whether to kiss or kill you,” he slurred.

He was out of his wits with drink and pain, but his words still sent a jolt through her that almost rivalled the uisge beatha for effect. “Perhaps you should just thank me,” she said, and left the bedside before he could say anything else.

Three days later, Maude was able to pronounce that Fulke’s wound was healing cleanly, without signs of the dreaded wound fever. At first she had not been sure and had had to wait out the raging headache, the thirst and sickness caused by the after effects of his drinking such a large quantity of uisge beatha. Now, however, she was certain. Already he was proving to be a restless, irritable patient, refusing to stay abed and swallow his nostrums as instructed.

“I’m not a puling infant,” he snarled at the sight of Maude armed with a bowl of oxtail broth. “It’s my thigh that’s injured, not my stomach.”

He was fully dressed and sitting in the window embrasure, his leg stretched out in front of him. His tangled hair and a four-day growth of beard made him look like the outlaw he was rather than the polished knight.

Maude narrowed her eyes. He had already sent one of the maids out in tears that morning, and had been thoroughly insufferable ever since William had taken the men out on a ‘hunt’ after the breaking of fast. She knew that he saw it as his responsibility to lead them, and was not happy at being forced to delegate, but that did not mean he should take his ire out on those around him.

“It’s the state of your manners that concerns me the most,” she answered tartly and set the bowl down in front of him together with a small loaf. “Since everyone else is dining on oxtail broth, I do not see that you should object. “You cannot bring fifty fighting men into a small manor like this and expect to dine like a king every day.”

He gave her an angry scowl and drew himself up. “I will pay my way. The men have gone out foraging, as you well know.”

“Stealing from John, you mean.”

“Much less than he steals from me.” Grudgingly he tore a piece off the bread and dipped it in the broth. “Why bring it to my chamber,” he demanded. “I am quite capable of sitting in the hall with my aunt and whoever else remains.”

“Partly because I hoped you might still be abed,” Maude snapped, “and partly because no-one wants to sit at table with a boor.” She had intended staying with him to make sure he ate his broth. Since he seemed to have every intention of doing so and she found his behaviour objectionable, she abandoned her plan and stalked out. She would examine his leg later, and if she hurt him, she would not be contrite.

Too angry and exasperated to sit at table in the hall and make conversation with Emmeline, Maude fetched her bow and quiver from her chamber and went to practise her archery at the butts.

Fulke drank the broth which was excellent and full flavoured. He ate the bread and knew with annoyance at Maude and irritation at himself that she was right. He was being petulant, but only because he was bored, shut away in this chamber and treated as if his wits had bled out of the hole in his leg. He was a proud, active man, healthy and vigorous, and not within his living memory had he been confined to bed for more than a day. The thought of William out foraging at the head of the troop was enough to make him bite his nails ragged. It was true that his brother had learned a little more prudence along the tourney road, but not so much that Fulke trusted him without qualm.

Still, he should not have taken his frustration out on Maude. He owed her more than he could repay. Perhaps that was part of the reason that he had lashed out. He made an impatient sound at the thought, and decided on the instant to do something to amend both his behaviour and the situation.

Pulling himself up by the angle of the embrasure wall, he limped slowly and painfully to the entrance curtain. His lance was propped against a coffer nearby and he grasped it to use as a prop. His chamber was part of a large room divided by the curtain, the other section containing his aunt’s solar. A maid was busy weaving braid on a small loom, but his aunt was nowhere to be seen. Likely she was in the hall dining on her own broth and being regaled by Maude with the tale of his execrable behaviour.

It was that thought rather than the pain in his leg that made him grimace as he limped to the embrasure. The maid had opened the lower shutters to allow the power of daylight into the chamber. Fulke gazed out on herb beds and a green area beyond which the manor’s retainers used for battle training and archery practise.

A single bowman faced the straw butts, drawing and releasing with fluid ease. He narrowed his eyes, the better to focus on the distant figure. A bow woman he amended with surprise and admiration. Even from where he stood, he could see that Maude Walter was good.

Not without a little difficulty, Fulke negotiated the wooden external stairs at the end of the solar and descended to the courtyard below. It was a calm autumn day, the sky blue and deep, the air crisp as cider. There was a slight breeze, enough to ruffle his hair, but not sufficient to blow the arrows off their course as Maude sent them winging into the butt. He watched the sharp angle of her arm, the tilt of her head, the way her lips pursed on the draw and then released in an expression that was almost a kiss as she loosed all the pent up tension and let the arrow fly. Beauty controlling power. He felt the hair lift on the nape of his neck.

He limped between the herb beds until he reached the edge of the sward, then paused to gain his breath and recover from the pain.

She must have seen him from the corner of her eye, for she turned. Angry colour flooded her face and she lowered the bow, her next arrow un-nocked.

“I am glad that it was not you shooting at me from the walls of Whittington,” he said. “For I know I would be dead. You have a better eye than Alain, and he’s by far the keenest marksman among us.”

She shrugged. “I shoot finest when I’m angry.”

Fulke stirred his toe in the soft, thick pile of the grass. A beetle was toiling amongst the short blades, its body as glossy as polished dark leather. “As you have every right to be.” A glance at Maude from beneath his brows revealed that she was eyeing him warily, anger still apparent in the pursed set of her lips and the slight narrowing of her lids. Christ, she was lovely. It was all too easy to imagine her long-limbed and wild in his bed. He cleared his throat and quashed the thought. “Even since being bound in swaddling bands as an infant I have chaffed at confinement. I am sorry if I railed at you for what is none of your fault. Indeed, I owe you and my aunt a debt beyond all paying. I would not have you think me ungrateful.”

Her look told him that while she was a little mollified, she was not yet prepared to let him off the hook. “I don’t.” She walked up to the butt and tugged her arrows out. He looked at her straight back, the ripple of her linen veil at each jerk of effort. “But you’re still a mannerless boor,” she said on her return.

“If you gave me another chance, I could prove otherwise.”

Her lips curved. “How many chances do you want?” she asked sweetly.

Fulke gave her a questioning frown.

“On my wedding morn,” she said. “You took a whore beneath my bridal roof.”

“What?”

“Hanild. Was that her name?” She nocked an arrow and let fly into the heart of the target. Thud. As if it were her enemy’s heart.

He stared in astonishment. “And that has rankled with you all this time?”

“Should it not? I was a new bride, and you humiliated me!”

“I didn’t do it to humiliate you,” Fulke said on a rising note, “I did it because I…” He dug his fingers through his hair and bit back the rest of the sentence.

“Because what?”

He shook his head.

“No, tell me, I want to know.” A new arrow sat between the leather guards on her fingers.

Fulke swallowed. “Because as you say, you were a new bride – Theobald’s wife. And God help me, I wanted you.”

She lowered her eyes and studied the goose feather fletching as if it were of vast importance.

“Every man present was imagining himself in Theobald’s place – claiming your virginity, creating that bloody sheet, and I was no different.” He smiled, although the gesture did not reach his eyes. “I had no intention of insulting you when I took Hanild to my bed. She was there; I was in need, and at the time it seemed like a reasonable idea to a man who had almost lost his reason.”

It was her turn to swallow. He saw the ripple of her throat, the way she drew a sharp, small breath, and he realised that the incident must have meant far more to her than a brief moment of chagrin. Why else would she remember so small a detail as Hanild’s name? Why else hold it against him for so long? Perhaps the attraction was mutual. Perhaps that was why she was so hostile.

“The wanting has not gone away,” he said softly. “If anything, it is worse now than it was before because it has grown as we have done. But whatever you think of my manners, I honour you and I honour Theobald.” He drew a line of darker green in the moist grass with the haft of the lance, bisecting the yard of ground between him and Maude. “I will not step beyond the line, and neither will you,” he said. “But we both know it exists – don’t we?”

Trembling, she lifted her chin, her eyes as clear and hard as green glass. He saw the denial, the preparation of an angry rebuff.

“Or am I more honest than you?” he asked.

She put the arrow to the nock, raised the bow. “I love Theobald dearly, and my loyalty to him is firm as a rock,” she said in a quivering voice. “How dare you!”

“Because you wanted to know.” He spread his hands. “I love Theobald too, and I would not do anything to betray his trust in me.”

“Is lusting after his wife not a betrayal of his trust?”

“Not while neither of us crosses this line.” He smiled again, still without humour. “Call it courtly love. The giving of a token for the breaking of a tourney lance in the season. If you are going to shoot me, do it now. Pierce my heart a second time.”

“Go away! Maude hissed, tears glittering in her eyes.

Fulke regarded her sombrely. “I came to make my peace,” he said. “I did not intend this to happen, I swear it.”

“Please… just go!”

He did as she asked, but slowly. His leg was throbbing with the strain of standing for so long, and although the burden of confession had been taken off his mind, the weight of its consequence had just been added. Behind him, blind of all but instinct, Maude sent fletch after fletch into the heart of the straw butt.

Later that evening she came to his chamber. This time there was no bowl of broth in her hand for he had taken his evening meal of salt fish in the hall with his aunt, amid the constraints of propriety. It was Maude who had eaten in her own tiny chamber, pleading a headache.

He was briefly surprised to see her now, but then realised that he should have known. Running away was not in her nature. Right or wrong, she would rather stand and fight.

She approached the bench in the embrasure where he was sitting, and he saw that she was carrying a clay ointment pot and fresh swaddling bands.

“Is your headache improved my lady?” he enquired politely and cast his glance to the curtain, which she had left open for propriety’s sake, nipping in the bud any gossip that might arise from her being alone with him.

“A little. Your leg needs tending, and my head will bear up to the task better than your aunt’s stomach.”

She hooked up a footstool with her ankle and sitting down beside him, unfastened the pin securing his bandage. Obviously, she was not going to ask him to lie down on the bed. Too dangerous, he thought with a bleak and private smile. Who was to say she was not right?

With brisk competence, she tended the wound, remarking that it was healing well. Fulke had cautioned himself against reacting to her touch but there was no need. Her cold tone and practicality were so powerful a barrier that there was not the slightest reaction from his groin, lest it be a slight tightening and shrinking away. God knew what she might do with those sewing shears at her belt.

She refastened the bandage and sat back, folding her hands in her lap like a staid matron. Then she drew a deep breath and looked him in the face, her expression a heart-rending mingling of fear and courage.

“I have come to make my peace with you,” she announced. “And to be as truthful with you as you have been with me.”

He wondered how long she had sat alone with her ‘headache’ wrestling with what she was going to do and say. Suddenly he was almost afraid to hear it, but he had to listen, had to know.

“I do love Theo,” she said. “He is kind and generous and honourable, and I never think of the years between us, except to hope that he remains in good health.” Her tone grew vehement. “He is my friend, my companion, and I would give my life for him. I would not hurt or harm him in any way.”

“Neither would I.” But he could scarcely imagine Theobald being delighted at this conversation, or the one that had taken place at the archery butts. It was dangerous ground, thin, thin ice, and no retreat.

“You are right about the line, though,” she said, her voice now scarcely above a whisper. “And I am so afraid that one of us will step across and destroy everything. Theobald knows that something is wrong between you and me. He cannot understand why we avoid each other’s company, but one day I fear that he will see and know.” She folded her arms tightly across her breasts, protecting her body. “Is it love or lust? I do not know, because I do not know you. Perhaps it is no more than wishing after what you cannot have.”

He eyed her sombrely. Mayhap that was the way she felt; until today he had been good at keeping her out, but he had seen facets of Maude since her late childhood that made him certain of his own commitment. “Since the only way to find out is to cross the line and neither of us will do so, there is no remedy save to keep apart,” he said.

“Well that is simple enough,” she said with false brightness. “I am to join Theo at court and then we’re going to Ireland.”

He smiled grimly in response. “And I am going back into the forests, seeking thorns to put in King John’s side.”

They looked at each other, the unspoken knowledge between them that he was treading a dangerous path, possibly towards his own death. The keeping apart might be as final as eternity.

There was sudden noise in the courtyard, a groom shouting for torches and the clattering of many shod hooves. In the chamber doorway, Emmeline called excitedly to Fulke and Maude that the troop was home from its foray.

“I have to go.” She rose so quickly that she stumbled on the full hem of her gown. He grasped her hand to steady her, the force pulling her momentarily towards him, and now her touch streaked through him like fire. Teetering on the line, one hairline strand remaining. Another tug and she would be in his lap.

He snatched his hand away and waved it hard. “Go!” His voice was ragged. “You’ll be safe. I can’t run after you can I?”

With a gasp, she fled.

Leaning back, Fulke put his face in his hands and tried to summon the will necessary to greet and question his brothers.

Introduction

Introduction